背景

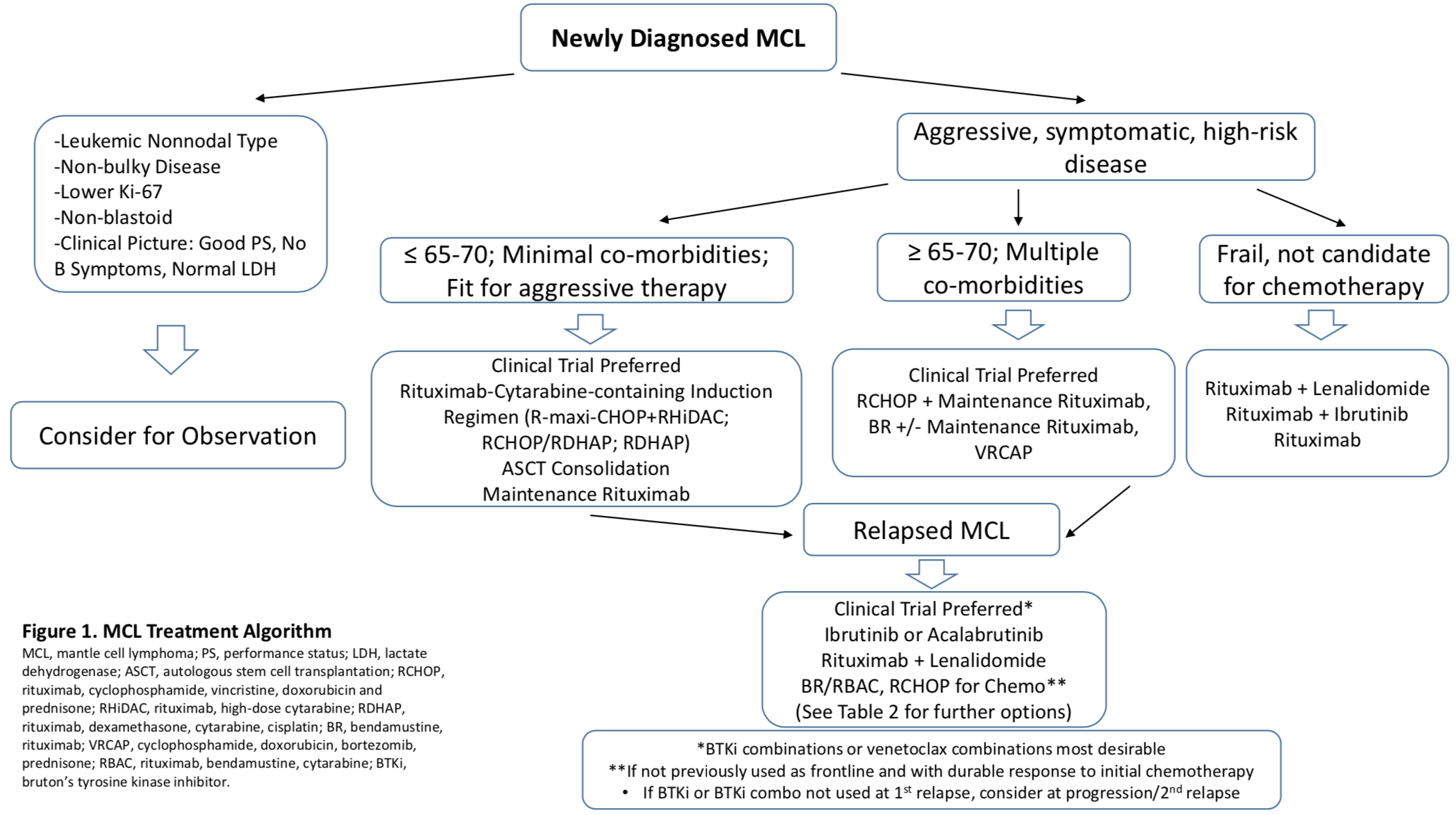

套细胞淋巴瘤(MCL)是一种罕见的B细胞非霍奇金淋巴瘤 (Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,NHL),约占所有NHL的6%。MCL患者具有特征性染色体移位t(11;14),即第14号染色体上免疫球蛋白重链基因和第11号染色体上Bcl-1基因之间移位,造成细胞周期蛋白D1(Cyclin D1)的组成型过表达。作为一种异质性疾病,MCL具有多种临床和生物学风险因素,那么针对这些风险因素,医学界已经给出了不同的治疗策略(图1)。尽管近年来对MCL生物学的理解有所提高,并且随着更为有效的药物的上市,MCL患者的生存率有所提高,但患者的总体预后仍然不佳。因此,更好地了解如何根据风险因素来选择新型药物对于进一步改善MCL的预后是至关重要的,鉴于此,美国俄亥俄州州立大学的Kami Maddocks 教授专门将近年来MCL的最新进展加以汇总,其最新论述已发表于最新出版的血液学权威杂志《BLOOD》之上[1]。

图1. 依据临床和生物学风险因素的治疗策略

疾病分类

最新的MCL分类来源于世界卫生组织(WHO)在2016年根据MCL发展的两种不同分子途径的定义,分为经典型MCL和白血病型非结节性MCL[2]。

经典型MCL由成熟B细胞组成,不通过生发中心发展,通常存在未突变或最小突变的免疫球蛋白重链可变区 (IgH variable region,IGHV)且SOX11阳性。主要发生于淋巴结和结外部位。这些肿瘤细胞易出现细胞周期失调、 DNA 损伤反应途径、细胞生存机制等,导致更加侵袭性的母细胞变异型 MCL(blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma,BV-MCL)和多形性变型 MCL(pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma,PMCL)的形成。

白血病型非结节性MCL通过生发中心发展,IGHV体细胞高频突变,SOX11阴性且遗传稳定。患者通常表现为外周血、骨髓和脾脏受累。白血病非节状MCL通常为惰性肿瘤,然而TP53继发性突变能够赋予肿瘤细胞较强的侵袭性。

预后风险分层

目前最重要的可用独立因素包括MCL 国际预后指数(mantle cell international prognostic index,MIPI)和细胞增殖指数 Ki67[3-5]。Hoster[6] 等评估了欧洲MCL试验的患者的生长模式、细胞学、MIPI联合细胞增殖指数 Ki67的预后影响,研究发现MIPI及Ki67为独立危险因素,从而定义了MIPI-c。结合MIPI和Ki-67,他们定义了4个风险组,5年OS分别为17%至85%,有利于指导筛选适合自体干细胞移植(ASCT)治疗的患者。

许多遗传异常与标准治疗的较差结果相关。研究发现TP53突变与母细胞变异形态、高Ki-67、高MIPI和高MIPI-c相关。携带TP53突变的患者接受诱导化疗及ASCT的预后均较差[7-8]。

淋巴瘤/白血病分子谱分析项目最近通过检测基因表达谱报道了MCL的增殖特征[9],该研究检测了110例接受R-CHOP治疗的MCL患者治疗前的石蜡包埋(FFPE)标本。基于可预测OS的增殖特征评分,110例接受R-CHOP方案化疗的患者被确定为高风险(26%),标准风险(29%)或低风险(45%)三个风险组,其OS分别为1.1,2.6和8.6年。这种增殖特征需要在更大样本量的试验以及前瞻性研究中进行验证并有望用于指导风险分层治疗。

新兴治疗策略

观察疗法

由于疾病进展迅速,大多数MCL患者在确诊时即需接受治疗,但少数呈惰性的患者可选择观察的等待。Martin等首先将初始治疗推迟3个月以上,这些患者的中位治疗时间(Median time to treatment,TTT)为12个月(4-128个月),其生存率优于诊断后3个月内开始治疗的患者[10]。其他回顾性研究也证实,尽管大多数患者需要进行治疗,但对于无症状和生物学特征的患者,观察疗法是合适的。

一线治疗

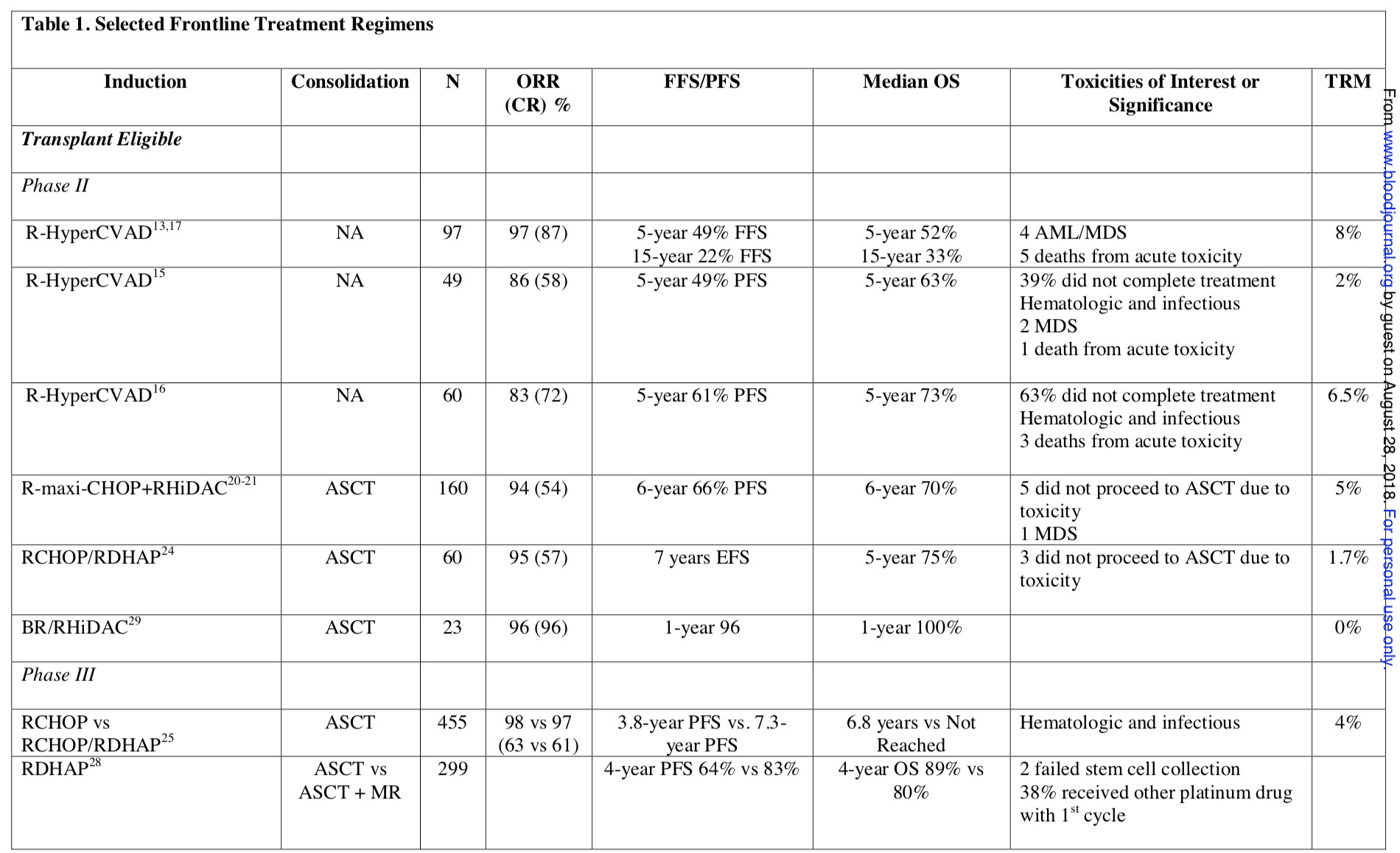

对于MCL,目前尚无标准的一线疗法。常用的一线化疗方案包括 CHOP方案(环磷酰胺、阿霉素、长春新碱、强的松)及R-CHOP方案(利妥昔单抗联合CHOP),HyperCVAD方案(环磷酰胺、长春新碱、阿霉素、地塞米松)及R-HyperCVAD方案(利妥昔单抗联合HyperCVAD)及BR方案(利妥昔单抗联合苯达莫司汀,但尚无治愈性的治疗方案(表1A)。目前的治疗策略是基于患者年龄和身体状况,年轻且相对健康的患者推荐实行含利妥昔单抗及阿糖胞苷的强化性化疗方案,后续可选择联合ASCT巩固,对于年老及身体状况较差的患者则推荐化学免疫联合治疗,后续可考虑利妥昔单抗维持(MR)。值得注意的是,随着新药伊布替尼纳入一线治疗阵营,微小残留病(MRD)阴性率得到了极大的提高,因此伊布替尼有望改写现有一线治疗的指南。

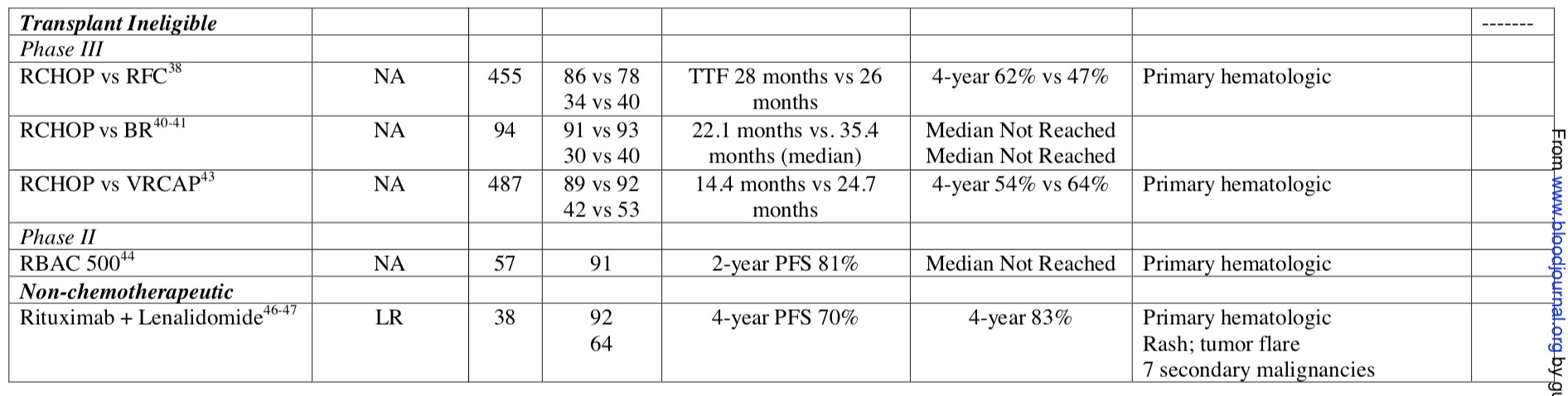

表1A. 适合干细胞移植患者的一线治疗策略及试验结果

表1B. 不适合干细胞移植患者的一线治疗策略及试验结果

年轻患者

近年,有三项独立的II期临床研究评估了R-HyperCVAD / MA方案(R-HyperCVAD与利妥昔单抗、高剂量甲氨蝶呤和阿糖胞苷交替使用)在年轻MCL患者中的有效性[11-14]。其中一项长达15年随访的研究显示,中位无失败生存期(FFS)为4.8年,OS为10.7年[11]。但其他两项多中心研究未能得到一致的结果,报告了显著的毒性[12-14]。为了尽量减少化疗毒性,安德森癌症中心在其研究中纳入50例患者,RI方案(利妥昔单抗联合伊布替尼)一线治疗后采用短疗程的R-HyperCVAD / MA治疗,其ORR率达100%,CR率高达80%[15]。

对于年轻患者,更常用的疗法是联合ASCT。北欧淋巴瘤组(NLG)和欧洲MCL网络的研究证实了几种移植前诱导方案的有效性。NLG[16-17]确定了阿糖胞苷在移植前诱导治疗中的重要地位,利妥昔单抗联合maxi-CHOP和大剂量阿糖胞苷交替,随后进行ASCT,结果显示6年PFS率为66%和6年OS率为70%。随访15年,中位PFS为8.5年,中位OS为12.7年,然而晚期复发患者的比率依然较高[18]。相同随访时间内,其疗效维持时间与R-HyperCVAD/MA[15]相当,但毒性较低。欧洲MCL[19]网络通过将患者随机分配至R-CHOP组或RCHOP / RDHAP组,随后进行ASCT,中位随访6.1年后,RCHOP / RDHAP组的TTF显著改善(9.1 vs 3.9,p = 0.038),确认了阿糖胞苷在ASCT之前的作用。

尽管阿糖胞苷的有效性是明确的,但是在最小化毒性的同时使疗效最大化的理想方案却需探索。评估利妥昔单抗联合大剂量阿糖胞苷(HDAC)的NLG MCL5试验由于不可接受的治疗失败率而提前终止[20]。淋巴瘤研究协会(LYSA)[21]评估了移植前的RDHAP诱导化疗的作用,除去烷化剂和蒽环类药物并将治疗限制在4个周期,结果显示RDHAP保持高反应率, 4年PFS和OS率分别为64%和80%,但尚未与RCHOP / RDHAP进行比较。Dana Farber癌症研究所的一II期研究评估3 周期BR+3周期RHDAC,随后进行ASCT的有效性,中位随访13个月,CR率和PFS率均为96%,但这项研究样本太小,随访有限[22]。华盛顿大学RHDAC与BR交替进行BR的单中心研究正在进行中(NCT02728531)。目前尚需要进行更大规模的多中心研究和更长时间的随访,以确认这种联合方案的疗效和持久性。

在评估ASCT巩固的唯一一项随机试验中,欧洲MCL网络对比了在CHOP样的方案诱导化疗后,ASCT与干扰素α(IFNα)维持的作用。ASCT组的PFS和OS均较IFNα组延长[23-24]。但当时利妥昔单抗尚未被纳入诱导治疗的方案中。近期一项多中心的回顾性研究纳入1007例年龄≤65岁的适合移植的MCL患者,其中64%的患者进行了ASCT,94%的患者接受力利妥昔单抗诱导化疗。在中位随访76.8个月(6.4年)时,ASCT组中位PFS(44 vs 75个月,p<0.01)和OS(115 vs147个月,p = 0.02)较利妥昔单抗组均延长[25]。

基于非移植方案中化学免疫治疗后MR的益处,LYSA组在其一项III期研究中评估了ASCT后MR的作用。 患者接受RDHAP序贯ASCT,然后随机为观察组及MR组,中位随访50.2个月,MR组的4年EFS(79% vs 62% p = 0.001),PFS(83% vs 64% p<0.001)和OS(89 %vs 80% p = 0.04)显著改善 [21]。

为了探索依鲁替尼在诱导化疗和维持治疗的应用以及ASCT在纳入靶向治疗中的作用。Triangle 研究(EudraCT:2014-001363-12)将患者随机分配到以下3组:(1)6个周期的RCHOP / RDHAP,序贯ASCT; (2)6个周期的RCHOP 联合依鲁替尼/ RDHAP,随后进行ASCT和2年依鲁替尼维持治疗(MI); 或(3)6个周期的RCHOP 联合依鲁替尼/ RDHAP和2年MI(NCT02858258),这将成为利妥昔单抗和阿糖胞苷诱导时代的第一个ASCT随机研究。

老年患者

大多数初治MCL患者的年龄较大,不能耐受化疗毒性,因此不推荐强化型免疫化疗方案或ASCT。欧洲MCL网络的II期临床研究证明,R-CHOP联合利妥昔单抗维持治疗(MR)方案可以作为这些患者的标准疗法,中位随访6.7年,相比于R-FC方案,R-CHOP / MR方案的PFS和OS显著延长,5年PFS率为51%,5年OS率为75%[26]。随机III期临床试验显示,与R-CHOP相比,BR患者的PFS显著延长,尽管OS没有差异,但BR方案毒性较低[27](表1B)。

鉴于BR方案的疗效和耐受性,研究者试图探索新的组合来改善该方案。意大利研究者在BR基础上联合低剂量阿糖胞苷,其2年PFS率达86%,但血液学毒性较大[28]。另一项多中心临床研究评估了来那度胺联合BR然后进行来那度胺维持治疗(ML)的有效性。中位随访31个月,中位PFS为42个月,3年OS为73%,但该方案毒性较大[29]。E1411 II期试验将患者随机分成四组(1)BR随后MR; (2)BR随后利妥昔单抗和来那度胺维持治疗(RL);(3)BR +硼替佐米(BRV),随后MR; (4)BRV随后RL(NCT01415752,旨在评估硼替佐米加入诱导化疗和来那度胺加入维持治疗中的作用。如何在改善预后的同时避免不可耐受的毒性作用是这些试验组合的一大挑战。MCL-R III期试验可通过评估含有阿糖胞苷诱导方案和含有来那度胺的维持治疗对使用RCHOP化疗的老年MCL患者的作用来解决这些问题。该试验将患者随机分为RCHOP与RCHOP/RHAD诱导化疗,第二次随机化为MR vs. RL(2012-002542-20)。

非化疗方法

MCL治疗的目标是延长疾病缓解同时尽量减少毒性,目前非化疗方法逐渐受到关注。一项多中心II期研究评估纳入38例患者,均接受来那度胺+利妥昔单抗诱导随后进行RL维持。2年PFS和OS分别为85%和97%,4年PFS和OS为69.7%和82.6%,36%的患者在5年后仍有缓解,但尚需与MR标准化疗免疫疗法进行比较[30-31]。利妥昔单抗+依鲁替尼+来那度胺(NCT03232307)的三联方案目前正在II期试验中进行评估,有望成为最佳治疗选择。

复发难治MCL

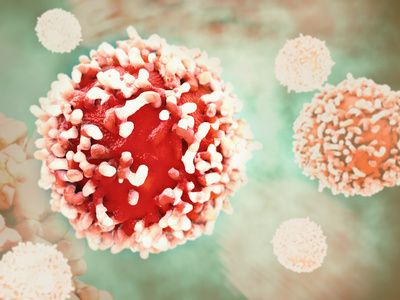

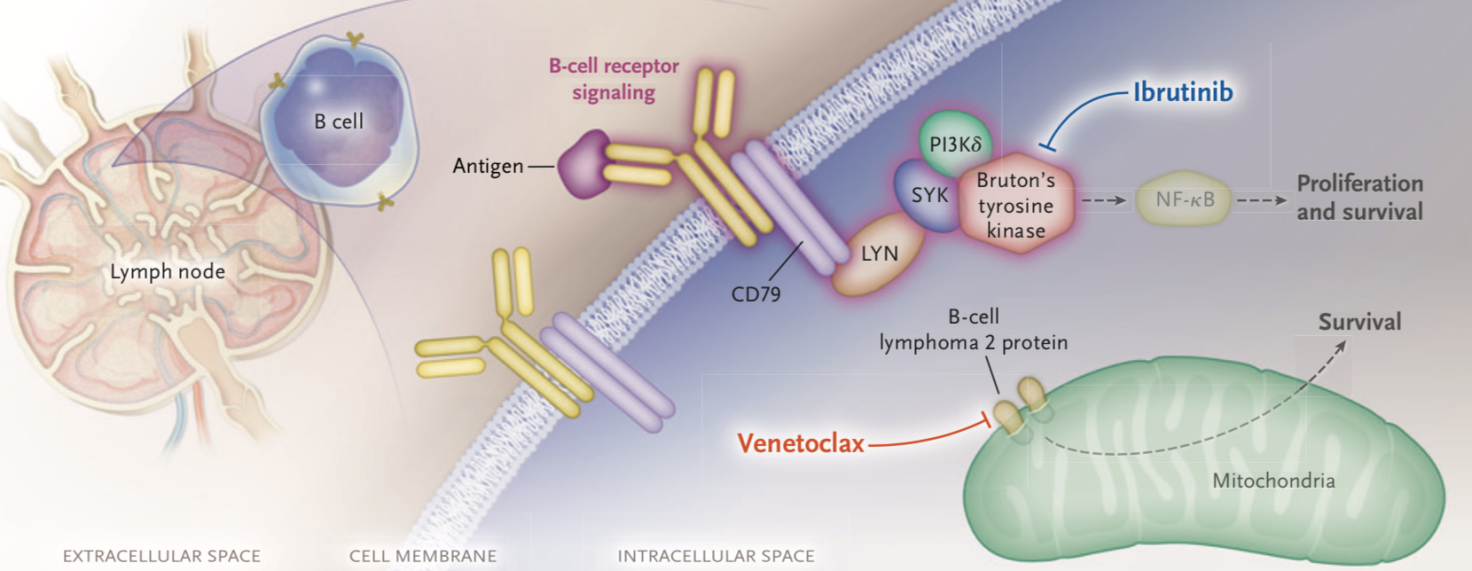

尽管目前一线疗法可以取得较高的反应率和PFS改善,患者病情仍有复发可能。复发难治MCL的治疗仍为一重大挑战。已获批的药物如硼替佐米、来那度胺和替西罗莫司的反应率低且疗效维持时间较短。目前推荐优选的治疗方案为BTK抑制剂,包括 ibrutinib 和 acalabrutinb,且以ibrutinib为基础的联合方案可能更优。(表2)。

作为第一个获得FDA批准用于MCL的口服靶向药物,伊布替尼展现了前所未有的单药活性:68%的ORR率、21%的CR率、中位PFS为13个月和中位OS为22.5个月[32-33]。伊布替尼整体耐受性良好,出血和房颤(AF)为潜在的主要不良反应事件(Aes)[33]。在一项随机III期试验中,与替西罗莫司相比,伊布替尼具有更好的ORR、更长的PFS和更好的耐受性[34]。首次复发时接受伊布替尼治疗的患者中位PFS为33.6个月,未达到中位OS,中位DOR为34.4个月,这些数据是接受其他疗法的复发患者的两倍,表明伊布替尼在复发后早期治疗的显著益处[35]。

虽然伊布替尼的有效性鼓舞人心,但仍有部分患者预后较差,因此探索伊布替尼的联合疗法以改善疗效及其持续时间更具临床意义。单中心II期试验中伊布替尼联合利妥昔单抗的方案达到了88%的ORR率和44%的CR率,Ki-67水平小于50%和大于50%的患者的反应率明显不同,ORR分别为100%和50%。中位随访47个月,58%的患者达到CR,中位PFS高达43个月。然而具有母细胞变异形态,高MIPI和高Ki-67的患者存活率较低,证实了在这些高风险患者中仍需要改善治疗[36]。伊布替尼、来那度胺和利妥昔单抗三联疗法的多中心II期试验(PHILEMON试验)的结果显示,ORR率为76%,CR率为56%,中位随访17.8个月,虽然有效性数据有所改善,但发生了3例与治疗相关的死亡[37]。由于CDK4/6抑制剂在MCL中的活性,理论上CDK4/6抑制剂(palbociclib)具有与伊布替尼的协同作用,与伊布替尼单药治疗相比,伊布替尼联合palbociclib方案取得了67%的ORR率和44%的CR率,同时具有更好的安全性[38]。

表2. 复发难治MCL的治疗策略

新药的进展

在多种新型药物的研究中,目前热门的疗法包括Acalabrutinib、口服bcl-2抑制剂venetoclax和CAR-T细胞。

基于最近发布的II期试验,Acalabrutinib于2017年10月下旬获得FDA批准用于复发MCL[39]。Venetoclax单药疗效显著,但venetoclax治疗易发生肿瘤溶解,用药期间需要进行密切监测[40]。II期临床试验报道了Venetoclax联合Ibrutinib 的ORR达71%,中位随访时间为15.9个月,中位PFS未达到,12个月和18个月PFS分别为75%和57%,但Ki-67≥30%的患者有效率较低(p = 0.02)[41-42]。Ibrutinib+安慰剂vs Ibrutinib+ venetoclax(NCT03112174)的III期研究正在进行中。

CAR-T细胞是过继性免疫治疗方法,对复发/难治性B细胞非霍奇金淋巴瘤(NHL)患者(包括少数MCL患者)表现出令人鼓舞的结果,最近FDA批准用于治疗复发性大细胞淋巴瘤[43-44]。 ZUMA-2试验(NCT02601313)目前正在评估自体CD-19 CAR-T构建体对伊布替尼治疗失败的复发/难治MCL患者的安全性和有效性。 CAR-T在MCL中的作用尚不清楚,但它为不适合移植的患者中提供了新的治疗选择。

结语

对于MCL,就一线治疗而言,BTK抑制剂伊布替尼凭借其显著的有效性有望改写现有一线疗法的规则;就复发患者而言,伊布替尼单药治疗和组合治疗方案展现了令人满意的有效性和可以接纳的安全性。因此可以预见的是,不同阶段的MCL患者均能够从伊布替尼的治疗中获得临床益处。Ibrutinib后复发或进展与预后不良有关,需要探索新的联合治疗以改善疗效。Venetoclax以及CAR-T等非化疗疗法提供了潜在的治疗选择,但MCL中存在有限的数据,且毒性较大,经济负担重。未来的试验应旨在提供基于疾病行为和生物学的治疗,纳入新的治疗组合,并利用风险分层工具来定制个体化治疗方案,达到更高的缓解率。

参考文献

[1] Maddocks, Kami. "Update on Mantle Cell Lymphoma." Blood (2018): blood-2018.

[2]Swerdlow S, Campo E, Pileri, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375-2390. 3

[2] Martin, Peter, et al. "Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma." J Clin Oncol 27.8 (2009): 1209-1213.

[3] Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111(2):558-565.

[4] Martinez A, Bellosillo B, Bosch F, et al. Nuclear surviving expression in mantle cell lymphoma is associated with cell proliferation and survival. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(2):501-510.

[5] Raty R, Franssila K, Joensuu H, et al. Ki-67 expression level, histological subtype, and the International Prognostic Index as outcome predictors in mantle cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69(1):11-20

[6]Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Francoise B, et al. Prognostic Value of Ki-67 Index, Cytology, and Growth Pattern in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma: Results From Randomized Trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol. 2016:34(12);1386-1394.

[7] Delfau-Larue M-H, Klapper W, Berger F et al. High-dose cytarabine does not overcome the adverse prognostic value of CDKN2A and TP53 deletions in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;126(5):604-611.

[8] Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al. TP53 mutations identify younger mantel cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 2017;130(17):19031910.

[9]Scott DW, Abrisqueta P, Wright GW, et al. New Molecular Assay for the Proliferation Signature in Mantle Cell Lymphoma Applicable to Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded biopsies. J Clin Oncol. 2016;35(15):1668-1677.

[10]Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009:27(8):1209-1213.

[11] Romaguera J, Fayad L, Rodriquez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 23(28):7013-7023, 2005. [12] Epner EM, Unger J, Miller T, Romzsa L, Spier C, Leblanc M, Fisher R. A multi-center trial of hyperCVAD + rituxan in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma. [abstract]. Blood. 2007; 110: 387.

[13] Bernstein SH, Epner E, Unger JM, et al. A phase II multicenter trial of hyperCVAD MTX/AraCand rituximab in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma; SWOG 0213. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(6): 1587-1593.

[14] Merli F, Luminari S, Ilariucci F, et al. Rituximab plus HyperCVAD Alternating with High Dose Cytarabine and Methotrexate for the initial treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma. A Multicenter Trial from GISL. Br J Haematol. 2012 156(3):346-353.

[15]Wang ML, Lee H, Thirumurthi S, et al. Ibrutinib-Rituximab followed by reduced chemoimmunotherapy consolidation in young, newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma patients: a Window of opportunity to reduce chemo. [abstract]. Hematological Oncology. 2017;35(S2):142143

[16]Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Nordic Lymphoma Group. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivopurged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized Phase II multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112(7):2687-2693.

[17] Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Nordic MCL2 trial update: six-year follow-up after intensive immunochemotherapy for untreated mantle cell lymphoma followed by BEAM or BEAC + autologous stem- cell support: still very long survival but late relapses do occur. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(3):355-362. 22

[18]Eskelund CW, Kolstad A, Jerkeman M, et al. 15-year follow-up of the Second Nordic Mantle Cell Lymphoma trial (MCL2): prolonged remissions without survival plateau. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(3):410-418.

[19]Pott C, Hoster E, Beldjord K, et al. R-CHOP/R-DHAP compared to R-CHOP induction followed by high dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation induces higher rates of molecular remission in MCL: results of the MCL younger intergroup trial of the European MCL Network [abstract]. Blood. 2010;116:965.

[20] Laurell A, Kolstad A. Jerkeman M, et al. High dose cytarabine with rituximab is not enough in first-line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma with high proliferation: early closure of the Nordic Lymphoma Group Mantle Cell Lymphoma 5 trial. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1206-1208.

[21]LeGouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L et al. Rituximab after Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1250-1260.

[22] Armand P, Redd R, Bsat J, et al. A phase 2 study of Rituximab-Bendamustine and RituximabCytarabine for transplant-eligible patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;173(1):89-95.

[23] Dreyling M, Lenz G, Hoster E, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progress-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the European MCL Network. Blood. 2005;105(7):2677-2684.

[24] Dreyling M, Lenz G, Schiegnitz, et al. Early consolidation by myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission significantly prolongs progress-free survival in mantle-cell lymphoma – Long Term Follow up of a Prospective Randomized Trial of the European MCL Network [abstract]. Blood. 2008;104:7.

[25] Gerson JN, Handorf E, Villa D, et al. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation Improves Overall Survival in Young Patients with Mantle Cell Lymphoma in the Rituximab Era. [abstract]. Blood. 2017;ASH Annual Meeting 341.

[26]. Kluin-Nelemans JC, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. R-CHOP Versus R-FC Followed by Maintenance with Rituximab Versus Interferon-Alfa: Outcome of the First Randomized Trial for Elderly Patients with Mantle Cell Lymphoma. [abstract]. Blood 2011;118:439.

[27] Rummel, Mathias J., et al. "Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial." The Lancet 381.9873 (2013): 1203-1210.

[28] Visco C, Chiappella A, Nassi L, et al. Rituximab, bendamustine, and low-dose cytarabine as induction therapy in elderly patients with mantle cell lymphoma: a multicenter, phase 2 trial from Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Lancet Hematol. 2017;4(1):e15-e23.

[29] Albertsson-Lindblad, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Lenalidomide-bendamustine-rituximab in patients older than 65 years with untreated mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2016:128(14)18141820.

[30] Ruan J, Martin P, Shah B, et al. Lenalidomide plus Rituximab as Initial Treatment for MantleCell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(19);1835-1844.

[31] Ruan J, Martin P, Christos PJ, et al. Initial Treatment with Lenalidomide Plus Rituximab for Mantle Cell Lymphoma: 5-Year Follow-up and Correlative Analysis from a Multi-Center Phase II Study. Blood. 2017;ASH Annual Meeting 154.

[32]Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantlecell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369(6):507-516.

[33] Wang ML, Blum KA, Martin P, et al. Long-term follow-up of MCL patients treated with singleagent ibrutinib: updated safety and efficacy results. Blood. 2015;126(6):739-745.

[34] Dreyling M, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al. Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10020):770-8.

[35] Rule, Simon, et al. "Outcomes in 370 patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib: a pooled analysis from three open‐label studies." British journal of haematology 179.3 (2017): 430-438.

[36] Jain, Preetesh, et al. "Four‐year follow‐up of a single arm, phase II clinical trial of ibrutinib with rituximab (IR) in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)." British journal of haematology (2018).

[37] Jerkeman, Mats, et al. "Ibrutinib, lenalidomide, and rituximab in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (PHILEMON): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial." The Lancet Haematology 5.3 (2018): e109-e116.

[38] Martin, Peter, et al. "A phase I trial of ibrutinib plus palbociclib in patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma." (2016): 150-150.

[39] Wang M, Rule S, Zinazni PL, et al. Acalabrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (ACE-LY-004); a single-arm, mulitcentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10121):659-667.

[40] Davids MS, Roberts AW, Seymour JF, et al. Phase I First-in-Human Study of Venetoclax in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(8):82633.

[41] Tam C, Roberts AW, Anderson MA. Combination Ibrutinib (IBR) and Venetoclax (VEN) for the Treatment of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL): Primary Endpoint Assessment of the Phase 2 AIM Study. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35:144-145.

[42]Tam CS, Anderson MA, Pott C, et al. Ibrutinib plus Venetoclax for the Treatment of Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(13):1211-1223.

[43] Kochenderfer JN, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, et al. Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):540-549.

[44] Kochenderfer JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, et al. Lymphoma Remissions Caused by Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Are Associated With High Serum Interleukin-15 Levels. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1803-1813.

如需了解更多淋巴瘤的前沿信息

请扫描二维码访问 “淋巴瘤亿刻 ”网站。

热门推荐

MORE

热门推荐

MORE

专家“亿”周谈——直击伊布替尼,纵观CLL治疗从免疫化疗到个体化靶向疗法的革新

07-09

J HEMATOL ONCOL:前瞻性研究预测伊布替尼治疗过程中房颤的发生

07-19

CANCER CHEMOTH PHARM :PH调节剂奥美拉唑对伊布替尼影响几何?

08-08

以数据为准绳,中国新药亟需更多原始创新!——首创BTK抑制剂伊布替尼原研专家潘峥婴专访

09-30

欧洲血液学杂志:TEC与BTK抑制剂出血副作用无关

10-22

2018年IWWM 会议现场直达:伊布替尼治疗华氏巨球蛋白血症突破性进展!

11-02

专家“亿”周谈—— J CLIN ONCOL:伊布替尼单药治疗症状型/初治型华氏巨球蛋白血症的最新突破

04-09

BLOOD:基于伊布替尼的联合方案治疗复发/难治CNS淋巴瘤效果显著

05-14

专家“亿”周谈——NEJM:伊布替尼联合维奈托克一线治疗慢性淋巴细胞白血病

06-12

【2019 ICML】黄慧强教授点评:IR联合短疗程R-HYPERCVAD / MTX在初治年轻MCL患者中有效性显著

06-20

【2019 EHA】纵览伊布替尼联合用药进一步提升CLL疗效

06-24

【2019 ICML】邱录贵教授点评:伊布替尼治疗华氏巨球蛋白血症的最新进展

06-25

【2019 ICML】张会来教授点评:伊布替尼联合利妥昔单抗治疗MCL疗效显著

06-25

【2019 ICML & EHA 回顾】中外专家畅谈伊布替尼治疗淋巴瘤的前沿进展

07-09Copyright 2008-2019 梅斯(MedSci)备案号 沪ICP备14018916号-1