《医疗和社会服务工作者预防工作场所暴力指南》(上)(美国劳工部职业安全与健康署制定)

2014-02-18 MedSci MedSci原创

医院暴力(Hospital violence)是工作场所暴力(Workplace violence)的一种形式,它的受害者可以是医疗场所内任何一位人员。医院暴力不仅仅威胁医生、护士,也可以危及医院管理人员、病人、病人家属乃至医院内的路人,所有在医院这一公共场所的人都可能是医院暴力的受害者。如果对医院暴力行为采取姑息态度,按照“破窗理论”,这种纵容会让更多的人受到伤害。美国劳工部关于工作场所暴力的预

医院暴力(Hospital violence)是工作场所暴力(Workplace violence)的一种形式,它的受害者可以是医疗场所内任何一位人员。医院暴力不仅仅威胁医生、护士,也可以危及医院管理人员、病人、病人家属乃至医院内的路人,所有在医院这一公共场所的人都可能是医院暴力的受害者。如果对医院暴力行为采取姑息态度,按照“破窗理论”,这种纵容会让更多的人受到伤害。美国劳工部关于工作场所暴力的预防指南中指出,如果可以确定工作场所暴力的危险因素,雇主采取适当的防范措施可以预防暴力的发生或者能将伤害降低到最低程度,其中最佳的预防措施就是对工作场所暴力采取零容忍政策。

要制定医院的工作场所暴力防范制度和计划;鼓励和支持医护人员对伤害事件的报告;预防和化解冲突或攻击性行为的方法;如何识别和处置敌意好斗之人以及非暴力性反应;愤怒管理技巧;解决冲突的技能与技巧;压力管理与放松技巧;保安制度与报警系统的使用;个人安全措施与自卫;对受害者的支持与救助等等。

以下是指南的全部内容,目前以英文为主。等待大家志愿翻译。

Contents:

Notice

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Overview of Guidelines

Violence Prevention Programs

Management Commitment and Employee Involvement

Worksite Analysis

Hazard Prevention and Control

Safety and Health Training

Recordkeeping and Program Evaluation

Conclusion

References

OSHA assistance

Safety and Health Program Management Guidelines

State Programs

Consultation Services

Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP)

Strategic Partnership Program

Alliance Programs

OSHA Training and Education

Information Available Electronically

OSHA Publications

Contacting OSHA

OSHA Regional Offices

Appendices Appendix A: Workplace Violence Program Checklists

Appendix B: Violence Incident Report Forms

Appendix C: Suggested Readings

Notice

These guidelines are not a new standard or regulation. They are advisory in nature, informational in content and intended to help employers establish effective workplace violence prevention programs adapted to their specific worksites. The guidelines do not address issues related to patient care. They are performance-oriented, and how employers implement them will vary based on the site's hazard analysis.

Violence inflicted on employees may come from many sources— external parties such as robbers or muggers and internal parties such as coworkers and patients. These guidelines address only the violence inflicted by patients or clients against staff. However, OSHA suggests that workplace violence policies indicate a zero-tolerance for all forms of violence from all sources.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act)(1) mandates that, in addition to compliance with hazard-specific standards, all employers have a general duty to provide their employees with a workplace free from recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm. OSHA will rely on Section 5(a)(1) of the OSH Act, the "General Duty Clause,"(2) for enforcement authority. Failure to implement these guidelines is not in itself a violation of the General Duty Clause. However, employers can be cited for violating the General Duty Clause if there is a recognized hazard of workplace violence in their establishments and they do nothing to prevent or abate it.

When Congress passed the OSH Act, it recognized that workers' compensation systems provided state-specific remedies for job-related injuries and illnesses. Determining what constitutes a compensable claim and the rate of compensation were left to the states, their legislatures and their courts. Congress acknowledged this point in Section 4(b)(4) of the OSH Act, when it stated categorically: "Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to supersede or in any manner affect any workmen's compensation law. . .."(3) Therefore, these non-mandatory guidelines should not be viewed as enlarging or diminishing the scope of work-related injuries. The guidelines are intended for use in any state and without regard to whether any injuries or fatalities are later determined to be compensable.

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed to these guidelines. They include health care, social service and employee assistance experts; researchers; educators; unions and other stakeholders; OSHA professionals; and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Also, several states have developed relevant standards or recommendations, such as California OSHA's CAL/OSHA Guidelines for Workplace Security and Guidelines for Security and Safety of Health Care and Community Service Workers; New Jersey Public Employees Occupational Safety and Health's Guidelines on Measures and Safeguards in Dealing with Violent or Aggressive Behavior in Public Sector Health Care Facilities; and the State of Washington Department of Labor and Industries' Violence in Washington Workplaces and Study of Assaults on Staff in Washington State Psychiatric Hospitals. Other organizations with relevant recommendations include the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations' Comprehensive Accreditation Manuals for Hospitals, the Metropolitan Chicago Healthcare Council's Guidelines for Dealing with Violence in Health Care, and the American Nurses Association's Promoting Safe Work Environments for Nurses. These and other agencies have information available to assist employers.

Introduction

Workplace violence affects health care and social service workers.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defines workplace violence as "violent acts (including physical assaults and threats of assaults) directed toward persons at work or on duty."(4) This includes terrorism as illustrated by the terrorist acts of September 11, 2001 that resulted in the deaths of 2,886 workers in New York, Virginia and Pennsylvania. Although these guidelines do not address terrorism specifically, this type of violence remains a threat to U.S. workplaces.

For many years, health care and social service workers have faced a significant risk of job-related violence. Assaults represent a serious safety and health hazard within these industries. OSHA's violence prevention guidelines provide the agency's recommendations for reducing workplace violence, developed following a careful review of workplace violence studies, public and private violence prevention programs and input from stakeholders. OSHA encourages employers to establish violence prevention programs and to track their progress in reducing work-related assaults. Although not every incident can be prevented, many can, and the severity of injuries sustained by employees can be reduced. Adopting practical measures such as those outlined here can significantly reduce this serious threat to worker safety.

Extent of the problem

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports that there were 69 homicides in the health services from 1996 to 2000. Although workplace homicides may attract more attention, the vast majority of workplace violence consists of non-fatal assaults. BLS data shows that in 2000, 48 percent of all non-fatal injuries from occupational assaults and violent acts occurred in health care and social services. Most of these occurred in hospitals, nursing and personal care facilities, and residential care services. Nurses, aides, orderlies and attendants suffered the most non-fatal assaults resulting in injury.

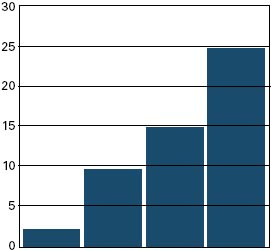

Injury rates also reveal that health care and social service workers are at high risk of violent assault at work. BLS rates measure the number of events per 10,000 full-time workers—in this case, assaults resulting in injury. In 2000, health service workers overall had an incidence rate of 9.3 for injuries resulting from assaults and violent acts. The rate for social service workers was 15, and for nursing and personal care facility workers, 25. This compares to an overall private sector injury rate of 2.

The Department of Justice's (DOJ) National Crime Victimization Survey for 1993 to 1999 lists average annual rates of non-fatal violent crime by occupation. The average annual rate for non-fatal violent crime for all occupations is 12.6 per 1,000 workers. The average annual rate for physicians is 16.2; for nurses, 21.9; for mental health professionals, 68.2; and for mental health custodial workers, 69. (Note: These data do not compare directly to the BLS figures because DOJ presents violent incidents per 1,000 workers and BLS displays injuries involving days away from work per 10,000 workers. Both sources, however, reveal the same high risk for health care and soical service workers.)

As significant as these numbers are, the actual number of incidents is probably much higher. Incidents of violence are likely to be underreported, perhaps due in part to the persistent perception within the health care industry that assaults are part of the job. Underreporting may reflect a lack of institutional reporting policies, employee beliefs that reporting will not benefit them or employee fears that employers may deem assaults the result of employee negligence or poor job performance.

| Incidence rates for nonfatal assaults and violent acts by industry, 2000 Incidence rate per 10,000 full-time workers |

|||||

|

|||||

| Private Sector Overall | Health Services Overall | Social Services | Nursing & Personal Care Facilities | ||

| Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2001). Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses, 2000. | |||||

The risk factors

Health care and social service workers face an increased risk of work-related assaults stemming from several factors. These include:

- The prevalence of handguns and other weapons among patients, their families or friends;

- The increasing use of hospitals by police and the criminal justice system for criminal holds and the care of acutely disturbed, violent individuals;

- The increasing number of acute and chronic mentally ill patients being released from hospitals without follow-up care (these patients have the right to refuse medicine and can no longer be hospitalized involuntarily unless they pose an immediate threat to themselves or others);

- The availability of drugs or money at hospitals, clinics and pharmacies, making them likely robbery targets;

- Factors such as the unrestricted movement of the public in clinics and hospitals and long waits in emergency or clinic areas that lead to client frustration over an inability to obtain needed services promptly;

- The increasing presence of gang members, drug or alcohol abusers, trauma patients or distraught family members;

- Low staffing levels during times of increased activity such as mealtimes, visiting times and when staff are transporting patients;

- Isolated work with clients during examinations or treatment;

- Solo work, often in remote locations with no backup or way to get assistance, such as communication devices or alarm systems (this is particularly true in high-crime settings);

- Lack of staff training in recognizing and managing escalating hostile and assaultive behavior; and

- Poorly lit parking areas.

In January 1989, OSHA published voluntary, generic safety and health program management guidelines for all employers to use as a foundation for their safety and health programs, which can include workplace violence prevention programs.(5) OSHA's violence prevention guidelines build on these generic guidelines by identifying common risk factors and describing some feasible solutions. Although not exhaustive, the workplace violence guidelines include policy recommendations and practical corrective methods to help prevent and mitigate the effects of workplace violence.

The goal is to eliminate or reduce worker exposure to conditions that lead to death or injury from violence by implementing effective security devices and administrative work practices, among other control measures.

The guidelines cover a broad spectrum of workers who provide health care and social services in psychiatric facilities, hospital emergency departments, community mental health clinics, drug abuse treatment clinics, pharmacies, community-care facilities and long-term care facilities. They include physicians, registered nurses, pharmacists, nurse practitioners, physicians' assistants, nurses' aides, therapists, technicians, public health nurses, home health care workers, social workers, welfare workers and emergency medical care personnel. The guidelines may also be useful in reducing risks for ancillary personnel such as maintenance, dietary, clerical and security staff in the health care and social service industries.

Violence Prevention Programs

A written program for job safety and security, incorporated into the organization's overall safety and health program, offers an effective approach for larger organizations. In smaller establishments, the program does not need to be written or heavily documented to be satisfactory.

What is needed are clear goals and objectives to prevent workplace violence suitable for the size and complexity of the workplace operation and adaptable to specific situations in each establishment. Employers should communicate information about the prevention program and startup date to all employees.

At a minimum, workplace violence prevention programs should:

- Create and disseminate a clear policy of zero tolerance for workplace violence, verbal and nonverbal threats and related actions. Ensure that managers, supervisors, coworkers, clients, patients and visitors know about this policy.

- Ensure that no employee who reports or experiences workplace violence faces reprisals.(6)

- Encourage employees to promptly report incidents and suggest ways to reduce or eliminate risks. Require records of incidents to assess risk and measure progress.

- Outline a comprehensive plan for maintaining security in the workplace. This includes establishing a liaison with law enforcement representatives and others who can help identify ways to prevent and mitigate workplace violence.

- Assign responsibility and authority for the program to individuals or teams with appropriate training and skills. Ensure that adequate resources are available for this effort and that the team or responsible individuals develop expertise on workplace violence prevention in health care and social services.

- Affirm management commitment to a worker-supportive environment that places as much importance on employee safety and health as on serving the patient or client.

- Set up a company briefing as part of the initial effort to address issues such as preserving safety, supporting affected employees and facilitating recovery.

The five main components of any effective safety and health program also apply to the prevention of workplace violence:

- Management commitment and employee involvement;

- Worksite analysis;

- Hazard prevention and control;

- Safety and health training; and

- Recordkeeping and program evaluation.

Management commitment and employee involvement are complementary and essential elements of an effective safety and health program. To ensure an effective program, management and frontline employees must work together, perhaps through a team or committee approach. If employers opt for this strategy, they must be careful to comply with the applicable provisions of the National Labor Relations Act.(7)

Management commitment, including the endorsement and visible involvement of top management, provides the motivation and resources to deal effectively with workplace violence. This commitment should include:

- Demonstrating organizational concern for employee emotional and physical safety and health;

- Exhibiting equal commitment to the safety and health of workers and patients/clients;

- Assigning responsibility for the various aspects of the workplace violence prevention program to ensure that all managers, supervisors and employees understand their obligations;

- Allocating appropriate authority and resources to all responsible parties;

- Maintaining a system of accountability for involved managers, supervisors and employees;

- Establishing a comprehensive program of medical and psychological counseling and debriefing for employees experiencing or witnessing assaults and other violent incidents; and

- Supporting and implementing appropriate recommendations from safety and health committees.

Employee involvement should include:

- Understanding and complying with the workplace violence prevention program and other safety and security measures;

- Participating in employee complaint or suggestion procedures covering safety and security concerns;

- Reporting violent incidents promptly and accurately;

- Participating in safety and health committees or teams that receive reports of violent incidents or security problems, make facility inspections and respond with recommendations for corrective strategies; and

- Taking part in a continuing education program that covers techniques to recognize escalating agitation, assaultive behavior or criminal intent and discusses appropriate responses.

Value of a worksite analysis

A worksite analysis involves a step-by-step, commonsense look at the workplace to find existing or potential hazards for workplace violence. This entails reviewing specific procedures or operations that contribute to hazards and specific areas where hazards may develop. A threat assessment team, patient assault team, similar task force or coordinator may assess the vulnerability to workplace violence and determine the appropriate preventive actions to be taken. This group may also be responsible for implementing the workplace violence prevention program. The team should include representatives from senior management, operations, employee assistance, security, occupational safety and health, legal and human resources staff.

The team or coordinator can review injury and illness records and workers' compensation claims to identify patterns of assaults that could be prevented by workplace adaptation, procedural changes or employee training. As the team or coordinator identifies appropriate controls, they should be instituted.

Focus of a worksite analysis

The recommended program for worksite analysis includes, but is not limited to:

- Analyzing and tracking records;

- Screening surveys; and

- Analyzing workplace security.

This activity should include reviewing medical, safety, workers' compensation and insurance records—including the OSHA Log of Work-Related Injury and Illness (OSHA Form 300), if the employer is required to maintain one—to pinpoint instances of workplace violence. Scan unit logs and employee and police reports of incidents or near-incidents of assaultive behavior to identify and analyze trends in assaults relative to particular:

- Departments;

- Units;

- Job titles;

- Unit activities;

- Workstations; and

- Time of day.

{nextpage}

Value of screening surveys

One important screening tool is an employee questionnaire or survey to get employees' ideas on the potential for violent incidents and to identify or confirm the need for improved security measures. Detailed baseline screening surveys can help pinpoint tasks that put employees at risk. Periodic surveys—conducted at least annually or whenever operations change or incidents of workplace violence occur—help identify new or previously unnoticed risk factors and deficiencies or failures in work practices, procedures or controls. Also, the surveys help assess the effects of changes in the work processes. The periodic review process should also include feedback and follow-up.

Independent reviewers, such as safety and health professionals, law enforcement or security specialists and insurance safety auditors, may offer advice to strengthen programs. These experts can also provide fresh perspectives to improve a violence prevention program.

Conducting a workplace security analysis

The team or coordinator should periodically inspect the workplace and evaluate employee tasks to identify hazards, conditions, operations and situations that could lead to violence.

To find areas requiring further evaluation, the team or coordinator should:

- Analyze incidents, including the characteristics of assailants and victims, an account of what happened before and during the incident, and the relevant details of the situation and its outcome. When possible, obtain police reports and recommendations.

- Identify jobs or locations with the greatest risk of violence as well as processes and procedures that put employees at risk of assault, including how often and when.

- Note high-risk factors such as types of clients or patients (for example, those with psychiatric conditions or who are disoriented by drugs, alcohol or stress); physical risk factors related to building layout or design; isolated locations and job activities; lighting problems; lack of phones and other communication devices; areas of easy, unsecured access; and areas with previous security problems.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of existing security measures, including engineering controls. Determine if risk factors have been reduced or eliminated and take appropriate action.

After hazards are identified through the systematic worksite analysis, the next step is to design measures through engineering or administrative and work practices to prevent or control these hazards. If violence does occur, post-incident response can be an important tool in preventing future incidents.

Engineering controls and workplace adaptations to minimize risk

Engineering controls remove the hazard from the workplace or create a barrier between the worker and the hazard. There are several measures that can effectively prevent or control workplace hazards, such as those described in the following paragraphs. The selection of any measure, of course, should be based on the hazards identified in the workplace security analysis of each facility.

Among other options, employers may choose to:

- Assess any plans for new construction or physical changes to the facility or workplace to eliminate or reduce security hazards.

- Install and regularly maintain alarm systems and other security devices, panic buttons, hand-held alarms or noise devices, cellular phones and private channel radios where risk is apparent or may be anticipated. Arrange for a reliable response system when an alarm is triggered.

- Provide metal detectors—installed or hand-held, where appropriate—to detect guns, knives or other weapons, according to the recommendations of security consultants.

- Use a closed-circuit video recording for high-risk areas on a 24-hour basis. Public safety is a greater concern than privacy in these situations.

- Place curved mirrors at hallway intersections or concealed areas.

- Enclose nurses' stations and install deep service counters or bullet-resistant, shatter-proof glass in reception, triage and admitting areas or client service rooms.

- Provide employee "safe rooms" for use during emergencies.

- Establish "time-out" or seclusion areas with high ceilings without grids for patients who "act out" and establish separate rooms for criminal patients.

- Provide comfortable client or patient waiting rooms designed to minimize stress.

- Ensure that counseling or patient care rooms have two exits.

- Lock doors to staff counseling rooms and treatment rooms to limit access.

- Arrange furniture to prevent entrapment of staff.

- Use minimal furniture in interview rooms or crisis treatment areas and ensure that it is lightweight, without sharp corners or edges and affixed to the floor, if possible. Limit the number of pictures, vases, ashtrays or other items that can be used as weapons.

- Provide lockable and secure bathrooms for staff members separate from patient/client and visitor facilities.

- Lock all unused doors to limit access, in accordance with local fire codes.

- Install bright, effective lighting, both indoors and outdoors.

- Replace burned-out lights and broken windows and locks.

- Keep automobiles well maintained if they are used in the field.

- Lock automobiles at all times.

Administrative and work practice controls affect the way staff perform jobs or tasks. Changes in work practices and administrative procedures can help prevent violent incidents. Some options for employers are to:

- State clearly to patients, clients and employees that violence is not permitted or tolerated.

- Establish liaison with local police and state prosecutors. Report all incidents of violence. Give police physical layouts of facilities to expedite investigations.

- Require employees to report all assaults or threats to a supervisor or manager (for example, through a confidential interview). Keep log books and reports of such incidents to help determine any necessary actions to prevent recurrences.

- Advise employees of company procedures for requesting police assistance or filing charges when assaulted and help them do so, if necessary.

- Provide management support during emergencies. Respond promptly to all complaints.

- Set up a trained response team to respond to emergencies.

- Use properly trained security officers to deal with aggressive behavior. Follow written security procedures.

- Ensure that adequate and properly trained staff are available to restrain patients or clients, if necessary.

- Provide sensitive and timely information to people waiting in line or in waiting rooms. Adopt measures to decrease waiting time.

- Ensure that adequate and qualified staff are available at all times. The times of greatest risk occur during patient transfers, emergency responses, mealtimes and at night. Areas with the greatest risk include admission units and crisis or acute care units.

- Institute a sign-in procedure with passes for visitors, especially in a newborn nursery or pediatric department. Enforce visitor hours and procedures.

- Establish a list of "restricted visitors" for patients with a history of violence or gang activity. Make copies available at security checkpoints, nurses' stations and visitor sign-in areas.

- Review and revise visitor check systems, when necessary. Limit information given to outsiders about hospitalized victims of violence.

- Supervise the movement of psychiatric clients and patients throughout the facility.

- Control access to facilities other than waiting rooms, particularly drug storage or pharmacy areas.

- Prohibit employees from working alone in emergency areas or walk-in clinics, particularly at night or when assistance is unavailable. Do not allow employees to enter seclusion rooms alone.

- Establish policies and procedures for secured areas and emergency evacuations.

- Determine the behavioral history of new and transferred patients to learn about any past violent or assaultive behaviors.

- Establish a system—such as chart tags, log books or verbal census reports—to identify patients and clients with assaultive behavior problems. Keep in mind patient confidentiality and worker safety issues. Update as needed.

- Treat and interview aggressive or agitated clients in relatively open areas that still maintain privacy and confidentiality (such as rooms with removable partitions).

- Use case management conferences with coworkers and supervisors to discuss ways to effectively treat potentially violent patients.

- Prepare contingency plans to treat clients who are "acting out" or making verbal or physical attacks or threats. Consider using certified employee assistance professionals or in-house social service or occupational health service staff to help diffuse patient or client anger.

- Transfer assaultive clients to acute care units, criminal units or other more restrictive settings.

- Ensure that nurses and physicians are not alone when performing intimate physical examinations of patients.

- Discourage employees from wearing necklaces or chains to help prevent possible strangulation in confrontational situations. Urge community workers to carry only required identification and money.

- Survey the facility periodically to remove tools or possessions left by visitors or maintenance staff that could be used inappropriately by patients.

- Provide staff with identification badges, preferably without last names, to readily verify employment.

- Discourage employees from carrying keys, pens or other items that could be used as weapons.

- Provide staff members with security escorts to parking areas in evening or late hours. Ensure that parking areas are highly visible, well lit and safely accessible to the building.

- Use the "buddy system," especially when personal safety may be threatened. Encourage home health care providers, social service workers and others to avoid threatening situations.

- Advise staff to exercise extra care in elevators, stairwells and unfamiliar residences; leave the premises immediately if there is a hazardous situation; or request police escort if needed.

- Develop policies and procedures covering home health care providers, such as contracts on how visits will be conducted, the presence of others in the home during the visits and the refusal to provide services in a clearly hazardous situation.

- Establish a daily work plan for field staff to keep a designated contact person informed about their whereabouts throughout the workday. Have the contact person follow up if an employee does not report in as expected.

Post-incident response and evaluation are essential to an effective violence prevention program. All workplace violence programs should provide comprehensive treatment for employees who are victimized personally or may be traumatized by witnessing a workplace violence incident. Injured staff should receive prompt treatment and psychological evaluation whenever an assault takes place, regardless of its severity. Provide the injured transportation to medical care if it is not available onsite.

Victims of workplace violence suffer a variety of consequences in addition to their actual physical injuries. These may include:

- Short- and long-term psychological trauma;

- Fear of returning to work;

- Changes in relationships with coworkers and family;

- Feelings of incompetence, guilt, powerlessness; and

- Fear of criticism by supervisors or managers.

Several types of assistance can be incorporated into the post-incident response. For example, trauma-crisis counseling, critical-incident stress debriefing or employee assistance programs may be provided to assist victims. Certified employee assistance professionals, psychologists, psychiatrists, clinical nurse specialists or social workers may provide this counseling or the employer may refer staff victims to an outside specialist. In addition, the employer may establish an employee counseling service, peer counseling or support groups.

Counselors should be well trained and have a good understanding of the issues and consequences of assaults and other aggressive, violent behavior. Appropriate and promptly rendered post-incident debriefings and counseling reduce acute psychological trauma and general stress levels among victims and witnesses. In addition, this type of counseling educates staff about workplace violence and positively influences workplace and organizational cultural norms to reduce trauma associated with future incidents.

Safety and Health Training

Training and education ensure that all staff are aware of potential security hazards and how to protect themselves and their coworkers through established policies and procedures.

Training for all employees

Every employee should understand the concept of "universal precautions for violence"— that is, that violence should be expected but can be avoided or mitigated through preparation. Frequent training also can reduce the likelihood of being assaulted.

Employees who may face safety and security hazards should receive formal instruction on the specific hazards associated with the unit or job and facility. This includes information on the types of injuries or problems identified in the facility and the methods to control the specific hazards. It also includes instructions to limit physical interventions in workplace altercations whenever possible, unless enough staff or emergency response teams and security personnel are available. In addition, all employees should be trained to behave compassionately toward coworkers when an incident occurs.

The training program should involve all employees, including supervisors and managers.

New and reassigned employees should receive an initial orientation before being assigned their job duties. Visiting staff, such as physicians, should receive the same training as permanent staff. Qualified trainers should instruct at the comprehension level appropriate for the staff. Effective training programs should involve role playing, simulations and drills.

Topics may include management of assaultive behavior, professional assault-response training, police assault-avoidance programs or personal safety training such as how to prevent and avoid assaults. A combination of training programs may be used, depending on the severity of the risk.

Employees should receive required training annually. In large institutions, refresher programs may be needed more frequently, perhaps monthly or quarterly, to effectively reach and inform all employees.

What training should cover

The training should cover topics such as:

- The workplace violence prevention policy;

- Risk factors that cause or contribute to assaults;

- Early recognition of escalating behavior or recognition of warning signs or situations that may lead to assaults;

- Ways to prevent or diffuse volatile situations or aggressive behavior, manage anger and appropriately use medications as chemical restraints;

- A standard response action plan for violent situations, including the availability of assistance, response to alarm systems and communication procedures;

- Ways to deal with hostile people other than patients and clients, such as relatives and visitors;

- Progressive behavior control methods and safe methods to apply restraints;

- The location and operation of safety devices such as alarm systems, along with the required maintenance schedules and procedures;

- Ways to protect oneself and coworkers, including use of the "buddy system;"

- Policies and procedures for reporting and recordkeeping;

- Information on multicultural diversity to increase staff sensitivity to racial and ethnic issues and differences; and

- Policies and procedures for obtaining medical care, counseling, workers' compensation or legal assistance after a violent episode or injury.

Supervisors and managers need to learn to recognize high-risk situations, so they can ensure that employees are not placed in assignments that compromise their safety. They also need training to ensure that they encourage employees to report incidents.

Supervisors and managers should learn how to reduce security hazards and ensure that employees receive appropriate training. Following training, supervisors and managers should be able to recognize a potentially hazardous situation and to make any necessary changes in the physical plant, patient care treatment program and staffing policy and procedures to reduce or eliminate the hazards.

Training for security personnel

Security personnel need specific training from the hospital or clinic, including the psychological components of handling aggressive and abusive clients, types of disorders and ways to handle aggression and defuse hostile situations.

The training program should also include an evaluation. At least annually, the team or coordinator responsible for the program should review its content, methods and the frequency of training. Program evaluation may involve supervisor and employee interviews, testing and observing and reviewing reports of behavior of individuals in threatening situations.

Recordkeeping and Program Evaluation How employers can determine program effectiveness

Recordkeeping and evaluation of the violence prevention program are necessary to determine its overall effectiveness and identify any deficiencies or changes that should be made.

Records employers should keep

Recordkeeping is essential to the program's success. Good records help employers determine the severity of the problem, evaluate methods of hazard control and identify training needs. Records can be especially useful to large organizations and for members of a business group or trade association who "pool" data. Records of injuries, illnesses, accidents, assaults, hazards, corrective actions, patient histories and training can help identify problems and solutions for an effective program.

Important Records:

- OSHA Log of Work-Related Injury and Illness (OSHA Form 300). Employers who are required to keep this log must record any new work-related injury that results in death, days away from work, days of restriction or job transfer, medical treatment beyond first aid, loss of consciousness or a significant injury diagnosed by a licensed health care professional. Injuries caused by assaults must be entered on the log if they meet the recording criteria. All employers must report, within 24 hours, a fatality or an incident that results in the hospitalization of three or more employees.(8)

- Medical reports of work injury and supervisors' reports for each recorded assault. These records should describe the type of assault, such as an unprovoked sudden attack or patient-topatient altercation; who was assaulted; and all other circumstances of the incident. The records should include a description of the environment or location, potential or actual cost, lost work time that resulted and the nature of injuries sustained. These medical records are confidential documents and should be kept in a locked location under the direct responsibility of a health care professional.

- Records of incidents of abuse, verbal attacks or aggressive behavior that may be threatening, such as pushing or shouting and acts of aggression toward other clients. This may be kept as part of an assaultive incident report. Ensure that the affected department evaluates these records routinely. (See sample violence incident forms in Appendix B.)

- Information on patients with a history of past violence, drug abuse or criminal activity recorded on the patient's chart. All staff who care for a potentially aggressive, abusive or violent client should be aware of the person's background and history. Log the admission of violent patients to help determine potential risks.

- Documentation of minutes of safety meetings, records of hazard analyses and corrective actions recommended and taken.

- Records of all training programs, attendees and qualifications of trainers.

As part of their overall program, employers should evaluate their safety and security measures. Top management should review the program regularly, and with each incident, to evaluate its success. Responsible parties (including managers, supervisors and employees) should reevaluate policies and procedures on a regular basis to identify deficiencies and take corrective action.

Management should share workplace violence prevention evaluation reports with all employees. Any changes in the program should be discussed at regular meetings of the safety committee, union representatives or other employee groups.

All reports should protect employee confidentiality either by presenting only aggregate data or by removing personal identifiers if individual data are used.

Processes involved in an evaluation include:

- Establishing a uniform violence reporting system and regular review of reports;

- Reviewing reports and minutes from staff meetings on safety and security issues;

- Analyzing trends and rates in illnesses, injuries or fatalities caused by violence relative to initial or "baseline" rates;

- Measuring improvement based on lowering the frequency and severity of workplace violence;

- Keeping up-to-date records of administrative and work practice changes to prevent workplace violence to evaluate how well they work;

- Surveying employees before and after making job or worksite changes or installing security measures or new systems to determine their effectiveness;

- Keeping abreast of new strategies available to deal with violence in the health care and social service fields as they develop;

- Surveying employees periodically to learn if they experience hostile situations concerning the medical treatment they provide;

- Complying with OSHA and State requirements for recording and reporting deaths, injuries and illnesses; and

- Requesting periodic law enforcement or outside consultant review of the worksite for recommendations on improving employee safety.

Employers who would like help in implementing an appropriate workplace violence prevention program can turn to the OSHA Consultation Service provided in their State. To contact this service, see OSHA's website at www.osha.gov or call (800) 321-OSHA.

OSHA's efforts to help employers combat workplace violence are complemented by those of NIOSH, public safety officials, trade associations, unions, insurers and human resource and employee assistance professionals, as well as other interested groups. Employers and employees may contact these groups for additional advice and information. NIOSH can be reached toll-free at (800) 35-NIOSH.

Conclusion

OSHA recognizes the importance of effective safety and health program management in providing safe and healthful workplaces. Effective safety and health programs improve both morale and productivity and reduce workers' compensation costs.

OSHA's violence prevention guidelines are an essential component of workplace safety and health programs. OSHA believes the performance-oriented approach of these guidelines provides employers with flexibility in their efforts to maintain safe and healthful working conditions.

下部分见:

《医疗和社会服务工作者预防工作场所暴力指南》(下)(美国劳工部职业安全与健康署制定)

本网站所有内容来源注明为“梅斯医学”或“MedSci原创”的文字、图片和音视频资料,版权均属于梅斯医学所有。非经授权,任何媒体、网站或个人不得转载,授权转载时须注明来源为“梅斯医学”。其它来源的文章系转载文章,或“梅斯号”自媒体发布的文章,仅系出于传递更多信息之目的,本站仅负责审核内容合规,其内容不代表本站立场,本站不负责内容的准确性和版权。如果存在侵权、或不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系,我们将立即进行删除处理。

在此留言

#工作场所#

47

#社会#

46

谁来翻译??

201