【综述】| 免疫治疗肺癌诱发甲状腺功能异常的研究进展

2023-09-03 中国癌症杂志 中国癌症杂志 发表于陕西省

本文从发病率、发病机制、预测生物标志物及治疗等方面对PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂治疗肺癌诱发的甲状腺功能异常进行探讨。

[摘要] 免疫检查点抑制剂[主要是程序性死亡-1/程序性死亡配体-1(programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1,PD-1/PD-L1)抑制剂]已经逐渐成为晚期肺癌最具有前景的治疗手段。但临床医师对于免疫相关不良反应仍缺乏足够认识,免疫相关甲状腺功能异常(immune-related thyroid dysfunction,irTD)作为常见的免疫相关不良反应之一,严重时可能会危及生命。本文从发病率、发病机制、预测生物标志物及治疗等方面对PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂治疗肺癌诱发的甲状腺功能异常进行探讨。

[关键词] 免疫相关甲状腺功能异常;免疫检查点抑制剂;程序性死亡-1/程序性死亡配体-1抑制剂;肺癌

[Abstract] Immune checkpoint inhibitors [mainly programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors] have emerged as the most promising therapy in lung cancer treatment. However, clinicians still lack sufficient knowledge about immune-related adverse events. Immune-related thyroid dysfunction (irTD), one of the common immune-related adverse events, can be life-threatening in severe cases. This article discussed the thyroid dysfunction induced by PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in the treatment of lung cancer from the aspects of the incidence, pathogenesis, predictive biomarkers and treatment of irTD.

[Key words]Immune-related thyroid dysfunction; Immune checkpoint inhibitors; Programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1 inhibitors; Lung cancer

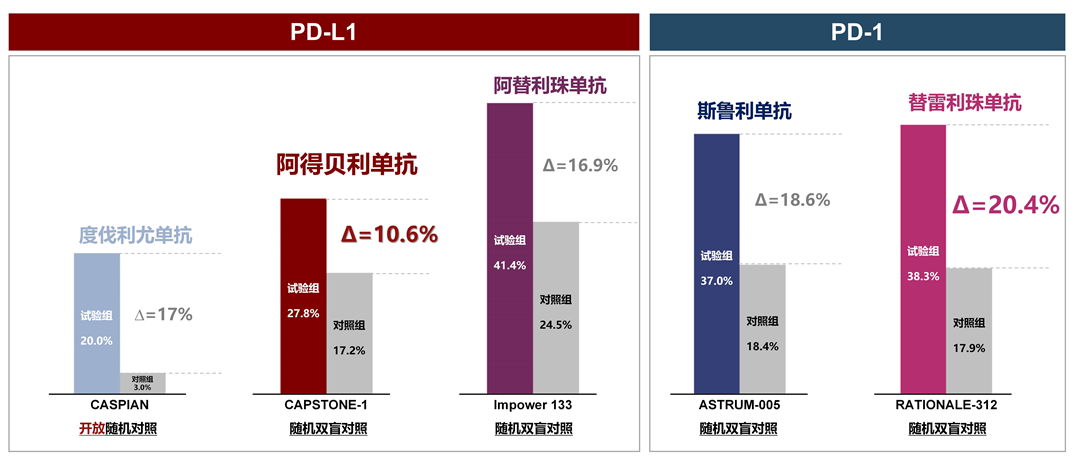

2020年全球癌症统计报告[1]显示,在所有癌症中,肺癌的死亡率最高。而在中国,肺癌是发病率和死亡率均最高的恶性肿瘤[2]。随着免疫治疗的迅速发展,免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitor,ICI)已经成为治疗驱动基因突变阴性的晚期非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer,NSCLC)及小细胞肺癌(small cell lung cancer,SCLC)的一种新兴方法。目前国内已获批可用于治疗肺癌的程序性死亡-1(programmed death-1,PD-1)抑制剂包括纳武利尤单抗(nivolumab)、帕博利珠单抗(pembrolizumb)、信迪利单抗(sintilimab)、替雷利珠单抗(tislelizumab)和卡瑞利珠单抗(camrelizumab),程序性死亡配体-1(programmed death ligand-1,PD-L1)抑制剂包括度伐利尤单抗(durvalumab)、阿替利珠单抗(atezolizumab)和舒格利单抗(sugemalimab)。但同时,免疫相关不良反应也因其高发生率逐渐引起关注,其中,免疫相关甲状腺功能异常(immune-related thyroid dysfunction,irTD)极为常见。尽管大部分irTD被认为危险程度较低,但严重irTD可能导致推迟甚至中止免疫治疗,从而使患者面临癌症进展的危险,因此全面了解irTD并及时鉴别诊断及预测尤为重要。

1 分类

irTD是指启动ICI治疗后,排除其他可能原因,出现2次或以上的甲状腺功能检查(thyroid function test,TFT)结果异常,主要可分为3种类型:

① 原发性甲状腺功能减退(临床或亚临床):可出现精神受损、体重增加、皮肤干燥、浮肿及心动过缓等症状,严重时还可出现黏液水肿性昏迷,TFT显示促甲状腺激素(thyroid stimulating hormone,TSH)升高,游离三碘甲状腺原氨酸(free thyronine 3,FT3)和游离甲状腺素(free thyroxine,FT4)降低或正常;② 原发性甲状腺功能亢进(临床或亚临床):可出现焦虑、食欲增加、体重下降、心悸、皮肤潮湿及心动过速等症状,严重时甚至会出现甲状腺危象,TFT显示TSH降低,FT3和FT4升高或正常;③ 甲状腺炎:常首先表现为短暂的甲状腺功能亢进,随后出现甲状腺功能亢进减退或发展为甲状腺功能减退。

2 发生率、严重程度及发生时间

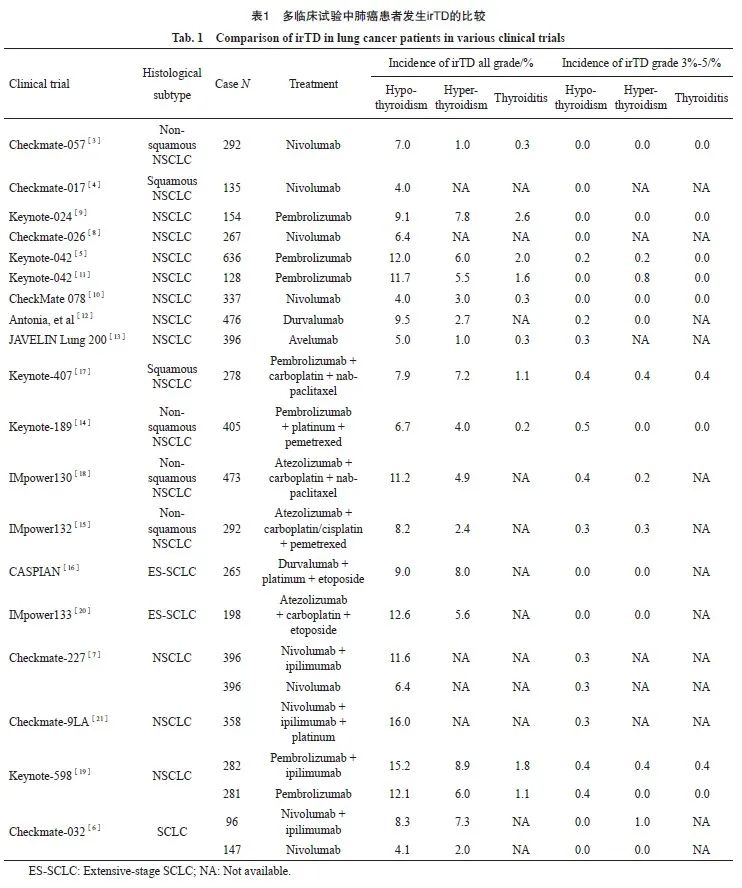

据报道,最常见的irTD是甲状腺功能减退,其次是甲状腺功能亢进,甲状腺炎发生较少。有多种因素可能会影响肺癌患者irTD的发生,主要取决于ICI类型和治疗方式。单用PD-1抑制剂诱发的甲状腺功能减退率为4.0%~12.1%,甲状腺功能亢进率为1.0%~7.8%,甲状腺炎率≤2.6%[3-11],而单用PD-L1抑制剂诱发的甲状腺功能减退率为5.0%~9.5%,甲状腺功能亢进率为1.0%~2.7%,甲状腺炎率≤0.3%[12-13]。近年来,多项研究[14-20]显示,PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂联合化疗诱发的irTD发生率与单用ICI相似,但PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂联合细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关抗原4(cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen-4,CTLA-4)抑制剂双免疫治疗诱发的irTD发生率却高于单用ICI,甲状腺功能减退率为8.3%~16.0%,甲状腺亢进率为7.3%~8.9%,甲状腺炎率≤1.8%[6-7,19,21]。

从严重程度上看,尽管irTD发生率较高,但大多数的irTD根据常见不良反应术语评定标准(Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events,CTCAE)5.0版[22]评定,危险等级≤2级。据报道,PD-1抑制剂单药治疗引起的3~5级甲状腺功能减退率为0.0%~0.4%[3-11],PD-L1抑制剂为0.2%~0.3%[12-13],PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂联合化疗为0.0%~0.5%[14-20],双免疫联合治疗为0.0%~0.4%[6-7,19,21],而关于3~5级甲状腺功能亢进及甲状腺炎发生率的数据较少(表1)。由此可以推断严重irTD的发生率并不高,且不同ICI和治疗方式对irTD的严重程度影响不大。然而,在临床应用ICI时,仍需对TFT进行定期监测并关注患者症状以避免严重irTD的发生,因为曾有研究[23]报道,肺癌患者在使用PD-1抑制剂后出现面部和舌头肿胀、言语不清等表现的严重黏液性水肿危象。

irTD多见于用药后的数周到6个月内,发生甲状腺功能亢进的中位时间较甲状腺功能减退早,出现TFT异常的中位时间较临床表现早[24]。发生irTD的时间为1.7~51.4周[3-4,25],发生甲状腺功能亢进的时间为21~59 d,发生甲状腺功能减退的时间为20~231 d[26]。至于单药ICI与免疫联合治疗诱发肺癌患者发生irTD的中位时间是否存在差异,鉴于现有研究纳入的样本量较少,尚无法比较,仍需进一步研究。

3 发病机制

ICI诱发irTD的发病机制尚未完全阐明。Kotwal等[27]采用流式细胞术分析发现,在irTD患者的血液样本中,某些T淋巴细胞(CD4+PD-1+ T淋巴细胞、CD8+PD-1+ T淋巴细胞、CD4+CD8+ T淋巴细胞)、自然杀伤(natural killer,NK)细胞及中间单核细胞均增加。在甲状腺样本中,T淋巴细胞总体、CD4-CD8- T淋巴细胞数量明显增加,CD8+ T淋巴细胞的比例也显著提高。

关于B细胞介导的体液免疫是否参与irTD的发生还未达成共识。Torimoto等[28]发现ICI治疗后,外周血中的滤泡辅助性T细胞、甲状腺球蛋白抗体(thyroglobulin antibody,TgAb)和甲状腺过氧化物酶抗体(thyroid peroxidase antibody,TPOAb)升高与irTD的发生密切相关。因此推测PD-1抑制剂可能通过抑制滤泡辅助性T细胞内的抑制信号,促使滤泡辅助性T细胞增殖从而导致大量自身抗体的形成。进一步研究[29-30]发现,TgAb可能是irTD发生的主要抗体。此外,Sabini等[31]研究还发现,TSH受体抗体也可能与irTD的发生相关。目前,对于甲状腺自身抗体升高是诱发甲状腺功能异常的原因还是破坏性甲状腺炎发展过程中释放甲状腺抗原而引发的体液免疫结果仍无定论[32]。但其他研究[33-34]却发现,许多发生irTD的患者甲状腺自身抗体呈阴性,推测irTD可能是通过一种抗体非依赖途径或由未知抗体引起的。除上述以外,Delivanis等[35]研究还发现,自身免疫应答可能通过增加外周血中CD56+ CD16+ NK细胞,减少不成熟CD56brCD16- NK细胞来参与irTD的发生。

irTD的另一种假说认为人类白细胞抗原-Ⅱ(human leukocyte antigen Ⅱ,HLA-Ⅱ)可能通过增加免疫基因易感性来提高T淋巴细胞对甲状腺的毒性作用。有研究[35]显示,在发生irTD的患者中,HLA-Ⅱ在CD14+ CD16+ 单核细胞中的表达显著提高,而低表达HLA-Ⅱ的免疫抑制单核细胞数量却显著下降。

除以上机制外,一些细胞及细胞因子在irTD的发生过程中也可能发挥作用。Kurimoto等[36]在发生irTD患者的外周血中,发现白细胞介素-2(interleukin-2,IL-2)升高而粒细胞集落刺激因子(granulocyte-colony stimulating factor,G-CSF)降低。由于辅助性T细胞2与G-CSF呈正相关,猜测G-CSF的降低可能与辅助性T细胞2活性降低有关。另一项研究[37]还发现,分泌IL-2的辅助性T细胞1数量增加。

4 生物标志物

目前,不少学者认为基线或ICI治疗期间甲状腺自身抗体的升高与irTD有关。在Keynote-001临床研究[26]中,出现抗PD-1相关甲状腺功能减退的NSCLC患者中有80%存在甲状腺抗体阳性,而38例未发生甲状腺功能减退的患者中仅有8%抗体阳性。Maekura等[38]也发现基线TgAb、TPOAb可作为预测抗PD-1相关甲状腺功能减退的重要因子。有研究[29-30]进一步证实,与基线TPOAb相比,基线TgAb在免疫相关甲状腺疾病中的作用更为重要。然而,也有研究得出相反的结论。Yoon等[39]纳入了184例接受免疫治疗的肺癌患者,发现甲状腺功能减退与基线TPOAb阳性和治疗期间TgAb阳性显著相关。需要注意的是,仅有小部分患者在基线或ICI治疗期间出现抗甲状腺抗体阳性,多数为阴性,而其他研究[35,40]也未发现抗甲状腺抗体与irTD之间的相关性。另外,基线TSH≥5 µU/mL也可能与irTD的发生有一定关系[29]。

18F-氟代脱氧葡萄糖(18F-fluorodeoxyglucose,18F-F DG)在正电子发射计算机体层成像(positron emission tomography and computed tomography,PET/CT)上的聚集常被用来判定人体内是否存在肿瘤或其他细胞快速分裂的部位,正常的甲状腺组织一般无18F-FDG摄取。Yamauchi等[30]研究发现,治疗前PET/CT提示甲状腺摄取18F-FDG水平弥漫性增加的肺癌患者在接受PD-1抑制剂治疗后更容易发生irTD,Kotwal等[41]的研究也得出类似结论。

除上述可能的生物标志物以外,年龄、性别、种族及体重指数(body mass index,BMI)等基本特征也被报道可能与irTD的发生有关。年龄、性激素可引起免疫系统紊乱,有研究[42]发现,年轻女性患者更有可能经历irTD。此外,BMI高的黑人患者也被发现易发生免疫相关甲状腺功能亢进[43-44]。

5 治疗与管理

美国临床肿瘤学会(American Society of Clinical Oncology,ASCO)与美国国立综合癌症网络(National Comprehensive Cancer Network,NCCN)联合发表的指南[45]建议:1级irTD患者可继续ICI治疗,对于没有心血管病史的亚临床或无症状患者无需任何干预,仅需每4~6周进行TFT。但若TSH>10 µU/mL则需补充甲状腺素以恢复到正常水平,值得注意的是,在开始补充甲状腺素之前,应排除并发肾上腺功能不全的情况;2级irTD患者可选择继续ICI治疗,但同时需对应补充甲状腺素或β受体阻滞剂直至症状缓解;≥3级irTD患者必须在停用ICI的同时予以补充甲状腺素或β受体阻滞剂治疗。其中,发生≥3级的免疫相关甲状腺功能亢进患者均需在4~6周后进行TFT,若仍提示甲状腺功能亢进,需行甲状腺摄取123I检查来确定是否存在其他非免疫相关甲状腺功能亢进疾病。irTD患者通常无需使用糖皮质激素,但对于伴有疼痛的甲状腺炎患者可根据症状及TFT结果按需使用,若效果不佳,可暂停ICI治疗直至症状消失后再考虑是否重新使用。

6 总结与展望

irTD的发生在ICI治疗肺癌期间很常见,其发病时间较早,病情一般较轻,发生率主要与治疗形式和ICI种类有关。免疫联合疗法诱发irTD的风险要明显高于单用ICI,PD-1抑制剂略高于PD-L1抑制剂。irTD的发病机制较为复杂,仍需进一步研究,而对能预测irTD的生物标志物也在不断探索中。尽管目前人们普遍认为irTD是可控的,但仍需警惕严重irTD的发生。临床医师应通过定期监测TFT及关注患者的临床表现来调整用药,避免因发生严重免疫相关不良反应和不恰当停药导致的疾病进展。

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

[参考文献]

[1] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL R L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA

Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249.

[2] 周彩存, 王 洁, 王宝成, 等. 中国非小细胞肺癌免疫检查点抑制剂治疗专家共识(2020年版)[J]. 中国肺癌杂志, 2021, 24(4): 217-235.

ZHOU C C, WANG J, WANG B C, et al. Chinese experts consensus on immune checkpoint inhibitors for non-small cell lung cancer (2020 version)[J]. Chin J Lung Cancer, 2021, 24(4): 217-235.

[3] BORGHAEI H, PAZ-ARES L, HORN L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(17): 1627-1639.

[4] BRAHMER J, RECKAMP K L, BAAS P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(2): 123-135.

[5] MOK T S K, WU Y L, KUDABA I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10183): 1819-1830.

[6] READY N E, OTT P A, HELLMANN M D, et al. Nivolumab monotherapy and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small cell lung cancer: results from the CheckMate 032 randomized cohort[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2020, 15(3): 426-435.

[7] HELLMANN M D, PAZ-ARES L, BERNABE CARO R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(21): 2020-2031.

[8] CARBONE D P. First-line nivolumab in stage Ⅳ or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Oncol Times, 2017, 39(17): 28-29.

[9] RECK M, RODRÍGUEZ-ABREU D, ROBINSON A G, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive nonsmall cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2016, 375(19): 1823-1833.

[10] WU Y L, LU S, CHENG Y, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in a predominantly Chinese patient population with previously treated advanced NSCLC: CheckMate 078 randomized phase Ⅲ clinical trial[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2019, 14(5): 867-875.

[11] WU Y L, ZHANG L, FAN Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pembrolizumab vs chemotherapy for previously untreated Chinese patients with PD-L1-positive locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: KEYNOTE-042 China study[J]. Int J Cancer, 2021, 148(9): 2313-2320.

[12] ANTONIA S J, VILLEGAS A, DANIEL D, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage Ⅲ non-small cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(20): 1919-1929.

[13] BARLESI F, VANSTEENKISTE J, SPIGEL D, et al. Avelumab versus docetaxel in patients with platinum-treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (JAVELIN Lung 200): an openlabel, randomised, phase 3 study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2018, 19(11): 1468-1479.

[14] GANDHI L, RODRÍGUEZ-ABREU D, GADGEEL S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 378(22): 2078-2092.

[15] NISHIO M, BARLESI F, WEST H, et al. Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of nonsquamous NSCLC: results from the randomized phase 3 IMpower132 trial[J]. J Thorac Oncol, 2021, 16(4): 653-664.

[16] PAZ-ARES L, DVORKIN M, CHEN Y B, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10212): 1929-1939.

[17] PAZ-ARES L, LUFT A, VICENTE D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non-small cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(21): 2040-2051.

[18] WEST H, MCCLEOD M, HUSSEIN M, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2019, 20(7): 924-937.

[19] BOYER M, ŞENDUR M A N, RODRÍGUEZ-ABREU D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus ipilimumab or placebo for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥ 50%: randomized, double-blind phase Ⅲ KEYNOTE-598 study[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2021, 39(21): 2327-2338.

[20]HORN L, MANSFIELD A S, SZCZĘSNA A, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer[J]. N Engl J Med, 2018, 379(23): 2220-2229.

[21]PROF, LUIS, PAZ-ARES, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2021, 22(2): 198-211.

[22]National Cancer Institute. Protocol development cancer therapy evaluation program[EB/OL]. (2017-11-27)[2023-04-28]. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm.

[23]KHAN U, RIZVI H, SANO D, et al. Nivolumab induced myxedema crisis[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2017, 5: 13.

[24]ZHOU N, VELEZ M A, BACHRACH B, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced thyroid dysfunction is a frequent event post-treatment in NSCLC[J]. Lung Cancer, 2021, 161: 34-41.

[25]YAMAZAKI H, IWASAKI H, YAMASHITA T, et al. Potential risk factors for nivolumab-induced thyroid dysfunction[J]. In Vivo, 2017, 31(6): 1225-1228.

[26]OSORIO J C, NI A, CHAFT J E, et al. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small cell lung cancer[J]. Ann Oncol, 2017, 28(3): 583-589.

[27]KOTWAL A, GUSTAFSON M P, BORNSCHLEGL S, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced thyroiditis is associated with increased intrathyroidal T lymphocyte subpopulations[J]. Thyroid, 2020, 30(10): 1440-1450.

[28]TORIMOTO K, OKADA Y, NAKAYAMADA S, et al. Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy induces Hashimoto’s disease with an increase in peripheral blood follicular helper T cells[J]. Thyroid, 2017, 27(10): 1335-1336.

[29]KIMBARA S, FUJIWARA Y, IWAMA S, et al. Association of antithyroglobulin antibodies with the development of thyroid dysfunction induced by nivolumab[J]. Cancer Sci, 2018, 109(11): 3583-3590.

[30]YAMAUCHI I, YASODA A, MATSUMOTO S, et al. Incidence, features, and prognosis of immune-related adverse events involving the thyroid gland induced by nivolumab[J]. PLoS One, 2019, 14(5): e0216954.

[31]SABINI E, SFRAMELI A, MARINÒ M. A case of drug-induced Graves’ orbitopathy after combination therapy with tremelimumab and durvalumab[J]. J Endocrinol Invest, 2018, 41(7): 877-878.

[32]ZHAN L, FENG H F, LIU H Q, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors-related thyroid dysfunction: epidemiology, clinical presentation, possible pathogenesis, and management[J]. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2021, 12: 649863.

[33]MAZARICO I, CAPEL I, GIMÉNEZ-PALOP O, et al. Low frequency of positive antithyroid antibodies is observed in patients with thyroid dysfunction related to immune check point inhibitors[J]. J Endocrinol Invest, 2019, 42(12): 1443-1450.

[34]YAMAUCHI I, SAKANE Y, FUKUDA Y, et al. Clinical features of nivolumab-induced thyroiditis: a case series study[J]. Thyroid, 2017, 27(7): 894-901.

[35]DELIVANIS D A, GUSTAFSON M P, BORNSCHLEGL S, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced thyroiditis: comprehensive clinical review and insights into underlying involved mechanisms[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2017, 102(8): 2770-2780.

[36]KURIMOTO C, INABA H, ARIYASU H, et al. Predictive and sensitive biomarkers for thyroid dysfunctions during treatment with immune-checkpoint inhibitors[J]. Cancer Sci, 2020, 111(5): 1468-1477.

[37]KRIEG C, NOWICKA M, GUGLIETTA S, et al. High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy[J]. Nat Med, 2018, 24(2): 144-153.

[38]MAEKURA T, NAITO M, TAHARA M, et al. Predictive factors of nivolumab-induced hypothyroidism in patients with non-small cell lung cancer[J]. In Vivo, 2017, 31(5): 1035-1039.

[39]YOON J H, HONG A R, KIM H K, et al. Characteristics of immune-related thyroid adverse events in patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors[J]. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul), 2021, 36(2): 413-423.

[40]DE FILETTE J, ANDREESCU C E, COOLS F, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endocrine-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors[J]. Horm Metab, 2019, 51(3): 145-156.

[41]KOTWAL A, KOTTSCHADE L, RYDER M. PD-L1 inhibitor-induced thyroiditis is associated with better overall survival in cancer patients[J]. Thyroid, 2020, 30(2): 177-184.

[42]CAMPREDON P, MOULY C, LUSQUE A, et al. Incidence of thyroid dysfunctions during treatment with nivolumab for non-small cell lung cancer: retrospective study of 105 patients[J]. Presse Med, 2019, 48(4): e199-e207.

[43]POLLACK R, ASHASH A, CAHN A, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced thyroid dysfunction is associated with higher body mass index[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2020, 105(10): dgaa458.

[44]D'AIELLO A, LIN J, GUCALP R, et al. Thyroid dysfunction in lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): outcomes in a multiethnic urban cohort[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2021, 13(6): 1464.

[45]彭 智, 袁家佳, 王正航, 等. ASCO/NCCN免疫治疗毒性管理指南解读[J]. 肿瘤综合治疗电子杂志, 2018, 4(2): 38-47.

PENG Z, YUAN J J, WANG Z H, et al. Comments on ASCO/NCCN management guidelines of toxicities from immunotherapy[J]. J Multidiscip Cancer Manag Electron Version, 2018, 4(2): 38-47.

本网站所有内容来源注明为“梅斯医学”或“MedSci原创”的文字、图片和音视频资料,版权均属于梅斯医学所有。非经授权,任何媒体、网站或个人不得转载,授权转载时须注明来源为“梅斯医学”。其它来源的文章系转载文章,或“梅斯号”自媒体发布的文章,仅系出于传递更多信息之目的,本站仅负责审核内容合规,其内容不代表本站立场,本站不负责内容的准确性和版权。如果存在侵权、或不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系,我们将立即进行删除处理。

在此留言