免疫治疗

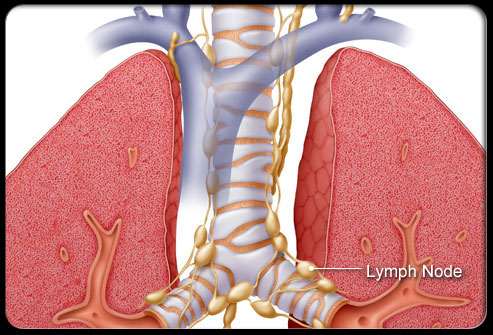

肿瘤微环境(TME)包括围绕肿瘤细胞的各种细胞类型、血管结构、信号分子和细胞外基质。其中,M2型肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(TAM)起着重要作用。单核细胞从血液中迁移时,会从癌细胞和癌相关成纤维细胞接收信号,并分化为M2型TAM,从而抑制免疫效应细胞,并招募其他免疫抑制细胞进入TME。其他免疫抑制性细胞包括与肿瘤相关的成纤维细胞、髓系细胞源性抑制细胞(MDSCs)、自然杀伤(NK)细胞、树突状细胞(DCs)、调节性淋巴细胞等。

目前的研究结果认为,先天免疫系统对肿瘤清除的贡献同样重要。NK细胞依赖于一个同时激活和抑制受体的“双重系统”,正常的NK细胞具有清除不表达MHC I类分子的肿瘤细胞并逃避淋巴细胞杀伤的能力,但当NK细胞被肿瘤浸润后,会导致其激活受体下调、细胞毒性降低[2],从而转向分泌免疫抑制性细胞因子,如VEGF、IL-10、TGF-β等。

由于肿瘤中的新生血管异常,肿瘤细胞对营养物质的竞争过于激烈,因此TME是一个缺氧、酸性、低糖的环境,对其他类型细胞而言生存非常困难。因此,由于其交织和重叠的特征,TME是一个阻碍免疫细胞的功能和生存能力的复杂环境。

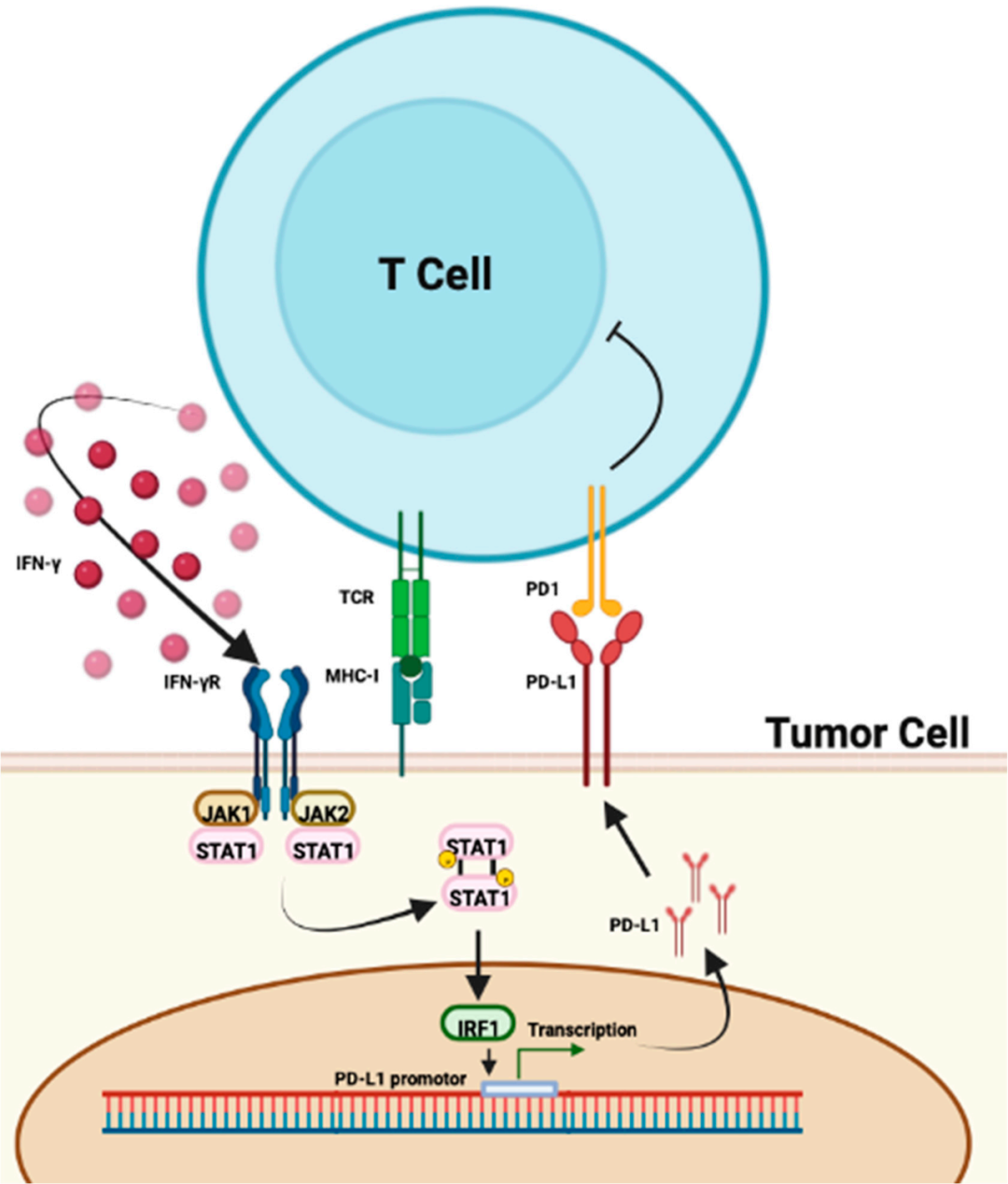

PD-L1是预测免疫治疗疗效的关键标志物[4],但在未表达PD-L1的患者中,仍有6.5%至10%的病例出现了应答[5-12]。

此外,由于肿瘤细胞本身和T淋巴细胞、抗原提呈细胞等免疫细胞的表达,PD-L1的作用变得难以解释,而且肿瘤异质性等相关因素还可能会导致PD-L1表达假阴性。

因此,PD-L1的表达并不能绝对准确地预测免疫治疗疗效。

图1:PD-1/PD-L1作用途径

肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞(TILs)是当前研究的热点。越来越多的研究发现,在诊断时通过分析肿瘤浸润性质可以预测免疫治疗疗效,从而指导治疗。

其中,调节性T细胞(T-regs)是CD4+ T淋巴细胞的亚群,通过分泌IL-10、IL-35和TGF-β来发挥抑制效应性T细胞反应的关键作用[13,14]。T-regs维持免疫稳态,而其他CD4+ T淋巴细胞则促进局部免疫反应。

此外,还有部分研究证实,高水平FoxP3和T-regs浸润的NSCLC与OS的不良预后相关。

人类白细胞抗原-I类分子(HLA-1)对NSCLC患者的影响呈现“多态性”。比如,Chowell等人的研究显示,HLA B44超型与OS改善相关,而HLA B62超型则与OS较低相关[15]。

此外,β-2-微球蛋白(B2M)的突变属于CMH-1,是向树突状细胞呈现抗原所必需的。因此,B2M的突变可谓改变了抗原呈现,这可能导致了ICIs的耐药性的产生[16]。

干扰素(IFN)是参与抗肿瘤免疫反应的重要分子。近期研究表明,IFN还可能是预测免疫治疗疗效的生物标志物。比如,Herbst等的研究发现,IFNγ高表达可能与黑色素瘤免疫治疗的完全缓解(CR)或部分缓解(PR)有关[17].在POPLAR试验中,IFNγ高表达与使用阿替利珠单抗治疗的NSCLC患者的OS改善相关[18]。

此外,IFN还是肿瘤发炎指数(TIS)的标志物之一[19,20],PD-L1的表达也可能与IFNγ密切相关[17-18]。

图2:IFN与PD-L1作用途径

中性粒细胞通过产生抑制淋巴细胞免疫活性的趋化因子和细胞因子,在肿瘤炎症的发生发展中也起着重要作用[21]。

因此,肿瘤环境中如果存在大量的中性粒细胞,则会产生炎症反应,导致癌细胞增殖和转移[22]。已有多篇大型系统性综述证实了中性粒细胞/淋巴细胞比值(NLR)在多种癌症中的预后价值,目前更易获得、更经济的NLR或将成为ICIs的预测生物标志物之一[23,24]。

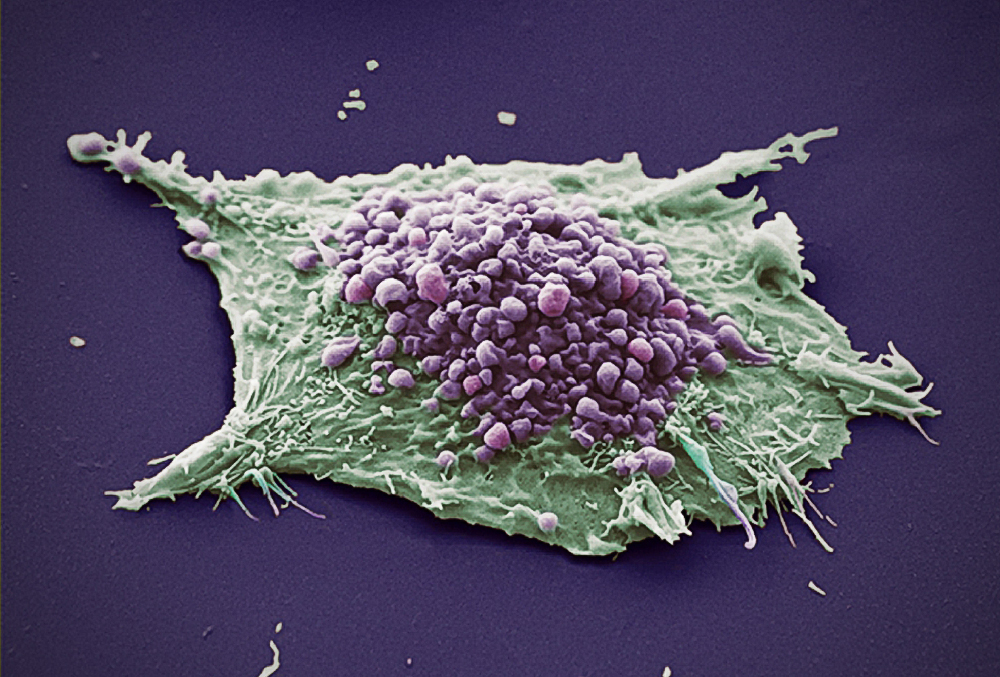

肿瘤突变负荷(TMB)是指肿瘤基因组去除胚系突变后的体细胞突变数量,这些突变会导致新抗原的产生,可被免疫系统识别并产生相关的抗肿瘤反应。

因此,当TMB较高(≥10mut/Mb)时,可能是ICIs有效性的一个预测因素[25-29]。但这一截断值并不绝对,可能取决于不同的基因组和所使用的分子技术,如WGS、WES、NGS等。

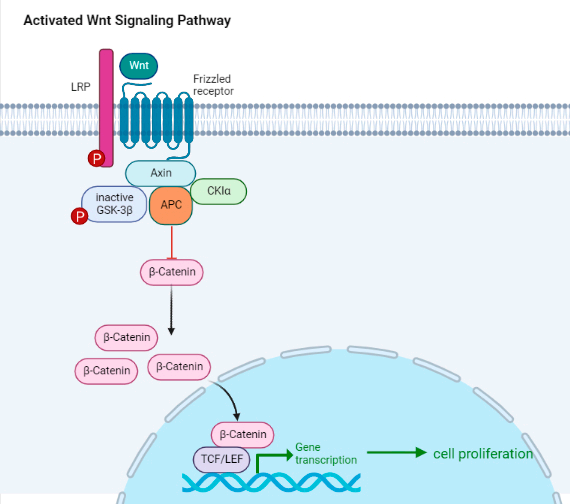

在NSCLC中,WNT/β-Catenin信号通路的激活与较高的TMB [30,31]和PD-L1低表达[32]相关,β-Catenin水平则似乎与TILs水平和CD11c+浸润水平呈负相关[31]。

此外,靶向WNT/β-Catenin信号通路联合ICIs治疗,可能是恢复T细胞浸润,从而保持免疫治疗敏感性的一种方法[33]。

图3:WNT/β-Catenin信号通路

已有研究表明,肠道微生物群可以调节适应性免疫和先天免疫,通过免疫刺激作用和其他复杂的机制,从而影响肿瘤微环境中的抗肿瘤免疫应答[34]。在过去的几年中,ICIs、抗生素(ATB)和质子泵抑制剂(PPI)的药物间相互作用逐渐被揭露,其中有一项Meta分析表明这些药物对ICIs的疗效有负面影响[35,36],但其余大多数是回顾性研究,因此仍有待更多前瞻性研究探寻其中机理。

除上述生物标志物外,使用人工智能(AI)算法来自动量化放射学特征的放射性生物标记物成为新的研究领域之一,其成像数据与组织的基因型和表型特征相关[37-42]。

此外,还一些研究表明,化疗可诱导免疫原性细胞死亡(ICD),从而增强免疫治疗的效果[43]。

PD-1和PD-L1免疫检查点抑制剂的诞生,极大程度上改变了NSCLC的治疗前景及其预后,但是并非所有患者最终从中真正受益。因此,识别出优势人群并预防潜在耐药性或不良反应显得尤为重要。目前,PD-L1表达作为NSCLC免疫治疗主要的预测生物标志物有一定的局限性,那么探寻新的有效生物标志物就成了当务之急,许多研究者们前赴后继地开展着相关研究,以期能够有新发现。

在NSCLC免疫治疗中,包括TMB、TILs、IFNγ、NLR,以及肠道微生物群等不同的生物标志物都可以作为ICIs的潜在预测指标,但目前没有达成统一的检测标准,甚至有一些研究结论互相矛盾。未来,相信随着前瞻性研究的进一步开展,能够验证出具有前景的预测和预后生物标志物,造福广大NSCLC患者。

参考文献(上下滑动)

[1] Lucile Pabst, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in the Era of Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Apr; 24(8): 7577.

[2] Russick, J.; Torset, C.; Hemery, E.; Cremer, I. NK cells in the tumor microenvironment: Prognostic and theranostic impact. Recent advances and trends. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 48, 101407.

[3] Wei, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, D. Emerging immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2021, 511, 68–76.

[4] Borghaei, H.; Gettinger, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Chow, L.Q.M.; Burgio, M.A.; de Castro Carpeno, J.; Pluzanski, A.; Arrieta, O.; Frontera, O.A.; Chiari, R.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes from the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 723–733.

[5] Borghaei, H.; Paz-Ares, L.; Horn, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Steins, M.; Ready, N.E.; Chow, L.Q.; Vokes, E.E.; Felip, E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1627–1639.

[6] Brahmer, J.; Reckamp, K.L.; Baas, P.; Crinò, L.; Eberhardt, W.E.E.; Poddubskaya, E.; Antonia, S.; Pluzanski, A.; Vokes, E.E.; Holgado, E.; et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 123–135.

[7] Herbst, R.S.; Baas, P.; Kim, D.-W.; Felip, E.; Pérez-Gracia, J.L.; Han, J.-Y.; Molina, J.; Kim, J.-H.; Arvis, C.D.; Ahn, M.-J.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1540–1550.

[8] Garon, E.B.; Rizvi, N.A.; Hui, R.; Leighl, N.; Balmanoukian, A.S.; Eder, J.P.; Patnaik, A.; Aggarwal, C.; Gubens, M.; Horn, L.; et al. Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2018–2028.

[9] Fehrenbacher, L.; Spira, A.; Ballinger, M.; Kowanetz, M.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Mazieres, J.; Park, K.; Smith, D.; Artal-Cortes, A.; Lewanski, C.; et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1837–1846.

[10] Massard, C.; Gordon, M.S.; Sharma, S.; Rafifii, S.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Luke, J.; Curiel, T.J.; Colon-Otero, G.; Hamid, O.; Sanborn, R.E.; et al. Safety and Effificacy of Durvalumab (MEDI4736), an Anti-Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced Urothelial Bladder Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3119–3125.

[11] Antonia, S.J.; Villegas, A.; Daniel, D.; Vicente, D.; Murakami, S.; Hui, R.; Yokoi, T.; Chiappori, A.; Lee, K.H.; de Wit, M.; et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1919–1929.

[12] Rebelatto, M.C.; Midha, A.; Mistry, A.; Sabalos, C.; Schechter, N.; Li, X.; Jin, X.; Steele, K.E.; Robbins, P.B.; Blake-Haskins, J.A.; et al. Development of a programmed cell death ligand-1 immunohistochemical assay validated for analysis of non-small cell lung cancer and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2016, 11, 95.

[13] Xiao, L.; Wei, F.; Liang, F.; Li, Q.; Deng, H.; Tan, S.; Chen, S.; Xiong, F.; Guo, C.; Liao, Q.; et al. TSC22D2 identifified as a candidate susceptibility gene of multi-cancer pedigree using genome-wide linkage analysis and whole-exome sequencing. Carcinogenesis 2019, 40, 819–827.

[14] Yarchoan, M.; Albacker, L.A.; Hopkins, A.C.; Montesion, M.; Murugesan, K.; Vithayathil, T.T.; Zaidi, N.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.A.; Frampton, G.M.; et al. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 126908.

[15] Chowell, D.; Morris, L.G.T.; Grigg, C.M.; Weber, J.K.; Samstein, R.M.; Makarov, V.; Kuo, F.; Kendall, S.M.; Requena, D.; Riaz, N.; et al. Patient HLA class I genotype inflfluences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science 2018, 359, 582–587.

[16] Ren, D.; Hua, Y.; Yu, B.; Ye, X.; He, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, J.; Mo, Y.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Predictive biomarkers and mechanisms underlying resistance to PD1/PD-L1 blockade cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 19.

[17] Herbst R.S., Soria J.-C., Kowanetz M., Fine G.D., Hamid O., Gordon M.S., Sosman J.A., McDermott D.F., Powderly J.D., Gettinger S.N., et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567.

[18] Fehrenbacher L., Spira A., Ballinger M., Kowanetz M., Vansteenkiste J., Mazieres J., Park K., Smith D., Artal-Cortes A., Lewanski C., et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1837–1846.

[19] Ott P.A., Bang Y.-J., Piha-Paul S.A., Razak A.R.A., Bennouna J., Soria J.-C., Rugo H.S., Cohen R.B., O’Neil B.H., Mehnert J.M., et al. T-Cell-Inflamed Gene-Expression Profile, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, and Tumor Mutational Burden Predict Efficacy in Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab Across 20 Cancers: KEYNOTE-028. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:318–327.

[20] Ayers M., Lunceford J., Nebozhyn M., Murphy E., Loboda A., Kaufman D.R., Albright A., Cheng J.D., Kang S.P., Shankaran V., et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 2017;127:2930–2940.

[21] Kim, R.; Emi, M.; Tanabe, K. Cancer immunoediting from immune surveillance to immune escape. Immunology 2007, 121, 1–14.

[22] Petrie, H.T.; Klassen, L.W.; Kay, H.D. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. J. Immunol. 1985, 134, 230–234.

[23] Guthrie, G.J.K.; Charles, K.A.; Roxburgh, C.S.D.; Horgan, P.G.; McMillan, D.C.; Clarke, S.J. The systemic inflflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: Experience in patients with cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2013, 88, 218–230.

[24] Templeton, A.J.; McNamara, M.G.; Šeruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocaña, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124.

[25] Xiao, L.; Wei, F.; Liang, F.; Li, Q.; Deng, H.; Tan, S.; Chen, S.; Xiong, F.; Guo, C.; Liao, Q.; et al. TSC22D2 identifified as a candidate susceptibility gene of multi-cancer pedigree using genome-wide linkage analysis and whole-exome sequencing. Carcinogenesis 2019, 40, 819–827.

[26] Yarchoan, M.; Albacker, L.A.; Hopkins, A.C.; Montesion, M.; Murugesan, K.; Vithayathil, T.T.; Zaidi, N.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.A.; Frampton, G.M.; et al. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight 2019, 4, 126908.

[27] Tu, C.; Zeng, Z.; Qi, P.; Li, X.; Guo, C.; Xiong, F.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, M.; Liao, Q.; Yu, J.; et al. Identifification of genomic alterations in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived Epstein-Barr virus by whole-genome sequencing. Carcinogenesis 2018, 39, 1517–1528.

[28] Rizvi, N.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Snyder, A.; Kvistborg, P.; Makarov, V.; Havel, J.J.; Lee, W.; Yuan, J.; Wong, P.; Ho, T.S.; et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015, 348, 124–128.

[29] Snyder, A.; Makarov, V.; Merghoub, T.; Yuan, J.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Desrichard, A.; Walsh, L.A.; Postow, M.A.; Wong, P.; Ho, T.S.; et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2189–2199.

[30] Takeuchi, Y.; Tanegashima, T.; Sato, E.; Irie, T.; Sai, A.; Itahashi, K.; Kumagai, S.; Tada, Y.; Togashi, Y.; Koyama, S.; et al. Highly immunogenic cancer cells require activation of the WNT pathway for immunological escape. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabc6424.

[31] Muto, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Mine, H.; Takagi, H.; Watanabe, M.; Inoue, T.; Yamaura, T.; Fukuhara, M.; Okabe, N.; et al. Tumor β-catenin expression is associated with immune evasion in non-small cell lung cancer with high tumor mutation burden. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 203.

[32] Kalbasi, A.; Ribas, A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 25–39.

[33] Li, X.; Xiang, Y.; Li, F.; Yin, C.; Li, B.; Ke, X. WNT/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway Regulating T Cell-Inflflammation in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2293.

[34] Peng, W.; Chen, J.Q.; Liu, C.; Malu, S.; Creasy, C.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Xu, C.; McKenzie, J.A.; Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; et al. Loss of PTEN promotes resistance to T cell-mediated immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 202–216.

[35] Fenton, T.M.; Jørgensen, P.B.; Niss, K.; Rubin, S.J.S.; Mörbe, U.M.; Riis, L.B.; Da Silva, C.; Plumb, A.; Vandamme, J.; Jakobsen, H.L.; et al. Immune Profifiling of Human Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Identififies a Role for Isolated Lymphoid Follicles in Priming of Region-Specifific Immunity. Immunity 2020, 52, 557–570.e6.

[36] Tsikala-Vafea, M.; Belani, N.; Vieira, K.; Khan, H.; Farmakiotis, D. Use of antibiotics is associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. IJID Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 2021, 106, 142–154.

[37] Chang, Y.; Lin, W.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Huang, C.-H.; Tzeng, H.-E.; Abdul-Lattif, E.; Wang, T.-H.; Tseng, T.-H.; Kang, Y.-N.; Chi, K.-Y. The Association between Baseline Proton Pump Inhibitors, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors, and Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 15, 284.

[38] Forget, P.; Khalifa, C.; Defour, J.-P.; Latinne, D.; Van Pel, M.-C.; De Kock, M. What is the normal value of the neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio? BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 12.

[39] Bagley, S.J.; Kothari, S.; Aggarwal, C.; Bauml, J.M.; Alley, E.W.; Evans, T.L.; Kosteva, J.A.; Ciunci, C.A.; Gabriel, P.E.; Thompson, J.C.; et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Amst. Neth. 2017, 106, 1–7.

[40] Mizuguchi, S.; Izumi, N.; Tsukioka, T.; Komatsu, H.; Nishiyama, N. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts recurrence in patients with resected stage 1 non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 13, 78.

[41] Takahashi, Y.; Horio, H.; Hato, T.; Harada, M.; Matsutani, N.; Morita, S.; Kawamura, M. Prognostic Signifificance of Preoperative Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer After Complete Resection. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22 (Suppl. 3), S1324–S1331.

[42] Scilla, K.A.; Bentzen, S.M.; Lam, V.K.; Mohindra, P.; Nichols, E.M.; Vyfhuis, M.A.; Bhooshan, N.; Feigenberg, S.J.; Edelman, M.J.; Feliciano, J.L. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio Is a Prognostic Marker in Patients with Locally Advanced (Stage IIIA and IIIB) Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Combined Modality Therapy. Oncol. 2017, 22, 737–742.

[43] Galluzzi, L.; Spranger, S.; Fuchs, E.; López-Soto, A. WNT Signaling in Cancer Immunosurveillance. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 44–65.

本网站所有内容来源注明为“梅斯医学”或“MedSci原创”的文字、图片和音视频资料,版权均属于梅斯医学所有。非经授权,任何媒体、网站或个人不得转载,授权转载时须注明来源为“梅斯医学”。其它来源的文章系转载文章,或“梅斯号”自媒体发布的文章,仅系出于传递更多信息之目的,本站仅负责审核内容合规,其内容不代表本站立场,本站不负责内容的准确性和版权。如果存在侵权、或不希望被转载的媒体或个人可与我们联系,我们将立即进行删除处理。

在此留言